One of the most immediate and obvious elements of an image of the future is technology1. It’s so natural for us to imagine how technology will be different in the future that sometimes that’s all we imagine. This is partly because technology is often much more visible/quantifiable than something like how water is governed, and partly because it’s cool and makes somebody lots of money. It hits that intersection of tangible and fast-changing enough to command attention.

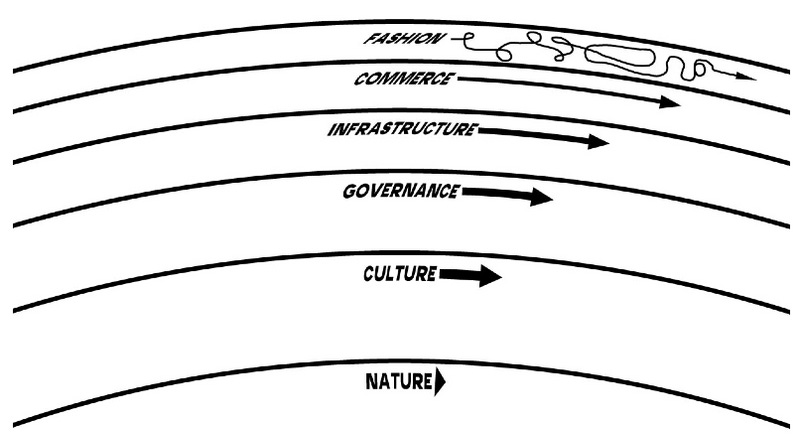

One concern is that technological change occurs in a disjointed way and in isolation, so it takes time for the rest of society to catch up. Social media is a good recent example — it connected people across the world via an algorithmic feed of content, and then we started feeling the political and mental health consequences and the result was greater government scrutiny and regulation. William Ogburn called this “cultural lag” a century ago and describes it as the result of the non-material world moving slower than the material world. Another way to articulate the same thing is to look once again at pace layers: technology that shows up in commerce and infrastructure will naturally outpace governance and culture. The friction between the lower layers’ inertia and the upper layers pulling is another way to conceptualize the lag2. The theory doesn’t resolve how much each will move in the end (toward ethical alignment or social surrender), but it does predict that the greater the mismatch, the more disruption will be caused.

One of the reasons technology is so disruptive and unpredictable is that its progress and adoption often follow an exponential growth pattern for a time. There are a couple of different mechanisms driving this; some of it is herd mentality (or a fear that ignoring this wave will lead to competitive disadvantage)3, and some of it is a genuine network effect, where increasing adoption increases the value of a tool. Some people today (Ray Kurzweil most notably) expect AI to continue to follow this exponential path to a point where it soon becomes impossible to further imagine the changes (the singularity), but of course most exponential change slows down based on the world’s inherent limitations4. History for Tomorrow’s 9th chapter focuses on AI as analogous to capitalism in its various facets, from financial (the interposition of AI inside existing work is similar to the trade in options, futures, debt bundles etc, and creates similar systemic risk) to industrial (in using AI, often people become more machine-like to fit in the system in ways similar to the advent of mass-production) to colonial (AI is hungry and is altering the planet to extract resources, from water to electricity to metal). Krznaric points to cooperative ownership enabled by government money and a new public movement demanding accountability from industry as elements of a path forward, but the enormous amount of up-front investment and the arms-race nature of the geopolitical equation make these seem impractical to me.

Usually I have a fairly expansive definition of technology — a human map or process for creating a set of artifacts via a set of inputs (natural resources, human effort and skill, and human artifacts). Thus, some of the most important technologies shaping our lives are language (sounds to convey thoughts and meaning), writing (marks and etches to create a longer-lasting physical representation of language), and agriculture (plowing, planting, weeding, and animal domestication to create a larger and more reliable food supply). But, in this article, I’ll be talking about technology more or less in the vague way it’s used in public discourse: “Technology is anything that wasn’t around when you were born” (Alan Kay?).

Gartner’s conceptualization of a “hype cycle” and attempts to locate specific technologies at different points of the cycle is an alternate conceptualization of this journey for technology, where early promise draws not only generic “hype” but a frenzy of investment by people looking for bigger returns than mature markets can offer. Over time the “magic” starts to look more like hard work, and there’s a strong correction before people learn how to actually get modest value out of the technology. This downplays the role of culture and governance, but shows exactly why things like Facebook start with an idea like “bringing the world closer together” (and may still believe it) but ends up being one more way to exchange ads for distraction.

This is currently causing a lot of investment in AI across businesses, despite a lack of clear results/value.

This is how Graham Molitor sees the world, as a series of sigmoid curves, but it’s also a basic idea in ecology.