Governing Water and Everything Else

(Sparing you a contrived soft introduction) Krznaric’s 5th chapter in History for Tomorrow is about how we govern limited water resources. The “tragedy of the commons”, despite being a relatively recent phrase, has such a hold in many circles that it’s considered not a possibility or even an argument but a truism: anytime property doesn’t have clear ownership, it will be tragically depleted as multiple actors working rationally create an outcome none of them want. But a “commons” doesn’t have to just mean a resource without an owner1; governance can preserve the shared resource, even in the absence of top-down authority2. In describing how commons can be governed effectively, Krznaric hews close to the framework laid out by Elinor Ostrom3: commons can effectively self-govern with community participation and clear in/out boundaries; rules that punish proportional to the offense, match reality, are respected externally, and exist in nested layers; and some mechanisms to monitor and resolve disputes. This has worked in different configurations in different societies, from Valencia’s centuries-old Tribunal of Waters to Bali, where water management is baked into their religion.

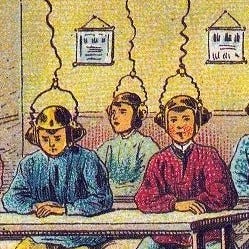

More broadly, in chapter 6 Krznaric indicts modern democracy as a system that is failing both in its ability to solve big problems and in the confidence of its citizens. He points out, though, that democracy, literally rule by the people, isn’t limited to the kind of indirect, elected-representative democracy that exists in either the American or Parliamentary configuration. He presents various configurations of two alternatives as inspiration for how we might improve democratic responsiveness and performance. The first changes the method of elections: rather than design systems to elect the “best” candidate, just pick names from the general public like jury duty4. This is sortition and it would create a world where (potentially) most people would be plucked from private life for a limited time to serve the public and then return back to their community. The second system is to eliminate elections entirely and have all citizens participate directly in the decision-making process. The ballot referendum is the baby version of this process, where the people directly enact a piece of legislation, but imagine people also directly involved in the design and debate about the wording of the laws. Where and how these could be fruitfully used is left as an exercise for the reader, innumerable implementation details would determine whether this would lead to disaster5, and the second- and third-order changes that would be made to accommodate these transformations would be key to their success, but! We really don’t have any excuse to look at the systems currently in place and think they’re the only way to run a democracy6.

The common thread between these two chapters actually fits very well with at least one of the core ideas of the American Revolution: decision-making should be decentralized to the smallest practical level rather than have rules arbitrarily imposed from above in the name of uniformity. Of course, there’s a reason the Founding Fathers put institutions in place to slow the work of democracy, and why we call the Western form of government “liberal democracy”: there are some rights/liberties7 that we want individuals to have regardless of whether the national or local majority support them, due to manipulation8, rashness9, or prejudice10.

Indigenous Culture and Stories

This article about how basic ideas of Māori culture affect the shape of culturally appropriate childhood education contains larger clues about how culture gives us a view of time and change that we don’t even notice. The first idea, wairua, is the interconnected flow of the physical and spiritual aspects of reality. We as people are entangled in both sides of this reality, as each of us enters the physical world from the spirit world (and will return upon death). Closely connected is whakapapa, an expansive genealogy situating individuals not only within human family/ancestry but also connecting to ancestral land and water11. Norms about the way things are to be done, tikanga, are manifested and passed down in several different wrappers: prayers (karakia), proverbs (whakataukī), and stories/myths/legends (pūrākau), such as the stories about Māui, that convey the virtues most valued by society.

Zoom out with me a moment on stories. Even in our lore-starved modern Western culture, our norms and values are transmitted through story12. This is, however, mostly the work of professionals operating at the national or global level — authors, filmmakers, etc. Because of this, this is the battlefield where so many conflicts about values play out, from whether Disney is ruining our childhoods to which books are allowed in schools (and who decides)13. This intentional refreshing of a culture’s myths and symbols to tell new stories isn’t just a Western issue: people in India are likewise trying to shift culture by changing the way the old stories are told and what they should mean14. The conflicts over who “owns” a civilization’s stories, what they are “allowed” to mean, and how those meanings evolve over time, are the visible signs of attempted cultural change happening in real time.

Bonus Content: Instant Podcasts

This has been bouncing around some of my circles in the past week, but seriously have you seen the NotebookLM podcast mode?! The tool itself allows you to upload documents and links to websites and then answer questions from them, write synthesis, etc. They just added the ability to generate a podcast about the sources that sounds like it could have come straight from NPR. Here’s what it sounds like pointed at my article (and all its sources) from last week:

Listening carefully, you can start to notice how the arguments don’t always flow, it doesn’t always pick the most relevant parts of documents, and there’s not always a strong throughline; the shocking thing is how the format of having one person sharing information and another person eagerly agreeing seduces us to lower our critical thinking. It also makes me wonder how much my own podcasting efforts sound just like this, but more importantly it shows how good AI is at transferring content from one format to another. If podcasts are an easier way for you to learn about things (because you have lots of time with free ears but not eyes, breaking ideas down makes them easier to digest, etc), try it the next time you have something you really want to understand (realizing that not all ideas can be properly conveyed in a 13-minute conversation).

And maybe it never did?

To be clear, top-down authority is certainly a viable strategy for maintaining water infrastructure, but is subject to changes in priority/focus by governments with many competing priorities.

Not too surprising, since she won a Nobel Prize for her work.

There are lots of other ways you could imagine deciding what names go into “the hat”: maybe just people who want to, or maybe you pick one person by district, interest group, etc. There isn’t an obviously right answer here — you’re balancing parsimony, different views of representation, etc.

For example, just replacing the current members of state legislators (or, Heaven forbid, Congress) with randomly selected members of the public would essentially put lobbyists in charge as the only people with enough experience to write and understand legislation.

I have an undergraduate degree in political science, so these aren’t new ideas to me, but I have to admit I got excited and started mapping out what it would take to change the Oregon constitution to have a sortition-and-assembly hybrid system to create laws. The urge faded.

Of course, what goes on this list changes over time and from place to place.

Indeed, Krznaric’s argument against electing representatives, that politicians can trick people into re-electing them even though their interests are being flouted, seems to clearly argue that popular decisions are often only tenuously connected to the public good.

This is a very old story: during the Peloponnesian War, Athens put down a revolt by Mytilene, then had to decide how to deal with the populace. The public assembly voted to kill all the men and enslave all the women and children, but then the next day, given time to reflect, they voted only to execute those most responsible, and had to send a ship to try to catch up with the first one that had received the annihilation orders (they succeeded).

Integration of public schools as a semi-recent American example.

These genealogies aren’t incidental, but structure Māori introductions — the person plus connections is the full person you are meeting.

I once told my pre-teen daughter, who thought that Hotel Transylvania was the pinnacle of cinema, that I was concerned about the core message that the first person you feel a spark of attraction toward is the only person you’ll ever be happy with, and you should go to any lengths to make it work. She looked me dead in the eye and said with barely contained pity, “oh Dad, movies don’t have messages!”

This is why arguments like “what’s the big deal, it’s just a kids movie” strike me as somewhere between naive and disingenuous.

Quick shout out here to RRR, possibly the best movie of the last 5 years. While watching, I had the experience of intuitively knowing that there was a mythological overlay on what was taking place, but not knowing how all the pieces fit together or what they meant.