Eliminating Waste and Division

Continuing our dive into History for Tomorrow, Krznaric’s third chapter tackles the environmental impact of our society’s fixation on consumption as a means to achieve status, and the damage all that making, buying, and throwing away does to our Earth’s strained systems. The alternative is to establish a regenerative economy, which takes the idea of the circular economy and adds in practices to actively heal and regenerate ecosystems and natural resources. One option is for people to naturally adopt lifestyles of simplicity; there is definitely a luxury aesthetic of simple living, but this seems unlikely to catch on. As an alternative, Krznaric cites the example of Edo period Japan, which shut itself off from outside trade and seriously degraded its resources (especially wood, needed for both building and fuel). In response, strict regulations were put in place to manage forests1 and ration wood, and entire industries sprang up not only to grow additional trees but also to repurpose and reuse everything from cloth scraps to candle wax. He proposes something similar, with regulations mandating things such as right to repair, congestion fees, banning of billboards to stop the stimulation of demand, and maybe even rationing and price controls, potentially directly tied to carbon emissions2. I don’t see an appetite for the level of authoritarianism Edo Japan required to implement something like this, especially in a world where the resources are still there but we know we need to save them for posterity.

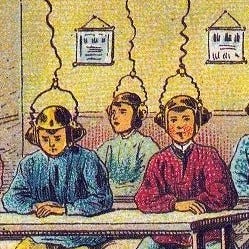

The fourth chapter traces the ills of social media from collaborative information networks dating to the time of the Roman Empire and especially the printing press, which dramatically spread knowledge and information but also created centuries of religious wars and panics about witches. However, the creation of printed pamphlets and newspapers enabled coffeehouses to become centers of news, conversation, and debate, creating the “public sphere” and the discourse necessary for democracy. Krznaric is confident that Web 2.0 can similarly be tamed, and he proposes lots of ideas for moving in this direction (listed here in decreasing order of practicality): requiring a small fee to set up an account, increasing the amount of moderation, breaking up the monolithic social media companies (and/or requiring profile/content portability), getting coffee shops to re-emphasize in-person interactions with strangers, and nationalizing social media. It seems to me that advances in communications technology effectively reduce the number and concentration of people needed to disrupt society, which inherently elevates certain ideas: the printing press enabled Protestantism not just because it was a different idea but because it was based on the concept that religion should be based on ideas and belief rather than belonging; the modern internet accelerates this and gives rise to (not just voice to) right-wing nihilism based on the idea that society is dead and strength is virtue. Thus, the next healthy stage of society may look very different than what we’ve seen in the past.

Side note: the further Krznaric gets, the more I appreciate the basic premise of his book. While I’m rarely convinced that his proposed solutions are practical (or a good idea), his willingness to break down what many people think of as a semi-hopeless polycrisis into constituent problems, with a conviction that each can be solved based on solutions to similar problems in the past, is deeply pragmatic and hopeful.

Values

One of the key elements of change in human societies3 is what members of the society deem important. This orientation (which exists in the minds of individuals but is also present in the logic of the institutions they build) is what we call values. Values are inherently many-dimensional, but enough of them tend to co-occur that people like imposing simplifying frameworks. The World Values Survey is one well-known approach, measuring people and comparing entire countries based on two dimensions: the importance of traditional sources of authority like religion, nation, and family; and the focus on security and cohesion vs tolerance and self-expression. Andy Hines’s work on values, on the other hand, lumps individuals into one of four clusters of values and posits that societies (while having a mix of the four types) progress through the sequence over time: Traditional (following the authoritative path), Modern (striving for economic and social achievement), Postmodern (creating meaning and a sense of belonging), and Integral (pragmatic use of values to improve overall systems).

Indigenous Futures

We also spent time reading about and discussing indigenous4 approaches to change. I’m immediately suspicious whenever people talk about indigenous cultures or knowledge or beliefs as monolithic. Often this is connected to indigenous people being wiser or more connected to the essence of humanity and the good life. This idea strongly rhymes with the “noble savage” trope that has infected Western thought for centuries. At its extreme, this leads to seeing them as essentially a part of the natural background rather than as full expressions of humanity, like de Tocqueville did with American Indians in chapter 1 of Democracy in America, where he describes them in his chapter about the geography of North America.

But indigenous cultures do provide incredible value for futurists5, because they preserve diversity in stories, ideas, and values that serve as a repository for humanity6. For one, their cultural values and practices date to a time before we experienced sustained economic growth, which could be an invaluable bridge to a potential degrowth or post-growth future. Many are naturally oriented toward sustainability based on something like the Seven Generations idea, echoing some orientations of Futures like longtermism. Additionally, they demonstrate the Western bias or lack of universality in lots of theories of change; for example, many indigenous cultures have a mix of values that don’t fit well into Hines’s categories or ideas about co-evolution with economic development. One idea I find especially compelling is that society should only be allowed to change as fast as we can develop lore (myths, stories, aphorisms, etc) that embed wisdom about how to act with new technology etc7.

So how can we engage indigenous peoples in Futures work in a way that is productive and doesn’t perpetuate the kind of harm suffered through colonization? This guide from Canadian and Australian indigenous scholars gives a general framework, but I’ll call out two very helpful ideas. First, working with the friendliest or most willing members of a community creates a selection bias that will harm the quality of the work. Second, don’t expect indigenous people to be impressed by your utopian images of the future — the last time people like you came around with grand visions of how to build an ideal society, it didn’t go well for these communities.

Japanese cultural values, such as the ability to act on the behalf of descendants, helped create markets for forests that hadn’t been planted yet, and contributed to the success of the overall project.

He proposes individual carbon cards to manage this, which made me think about the impact and waste involved in printing one of these for every American. Also, it does seem to maintain the framing that consumers are primarily to blame for the environmental impact of the products they buy. My brain has been turning on how to make it work, though — ask me about it sometime.

Depending on your theoretical orientation, a key cause or a key effect.

I wholly plan to sidestep the question of what we even mean by “indigenous peoples”. Even just comparing these definitions from the UN and Amnesty International, you’ll see some clear landmines. I’ll assume a vague consensus around who we’re talking about.

To be clear, the worth of people and their way of life aren’t measured by how they benefit me personally, but sometimes you get both.

A good example is the Potlatch, where status was gained or maintained by gift-giving, incentivizing redistribution of wealth and reciprocity.

See especially the second half of this interview with Aboriginal scholar Tyson Yunkaporta for a perspective on this.