I’m continuing the thread from last week by sharing and explaining 4 more archetypes of problems that can arise from specific system arrangements. Becoming familiar with these can help diagnose and treat issues in the systems around us. Again, see The Systems Thinker website for more detail.

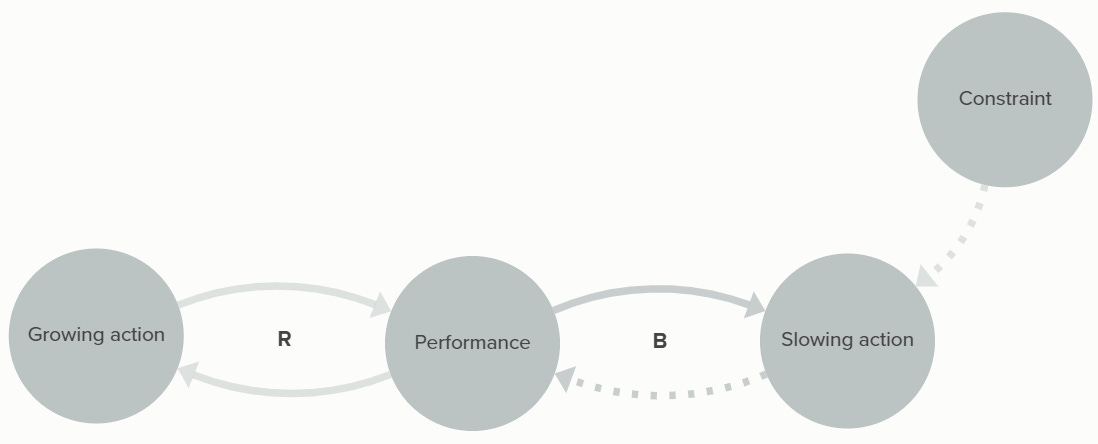

Limits to Success

The basic story here is that there is some external constraint that limits the behavior in the reinforcing loop on the left. For a consumer product this could be the total available market for a product; for a virus it would be the total population of potential hosts. As another example, think about the creation of useful software products by a team inside a company, where the constraint is the headcount: the products being well-built/well-received energizes the team and drives more action, but also creates additional need for maintenance of existing products that starts to cannibalize team attention.

The reinforcing loop on the left often follows a pattern of exponential growth; by measuring the doubling time of the process, you can get a sense of when the limits may become relevant. If you want to keep the growth going, finding ways to relax the constraint (finding new resources/markets/etc), minimize the impact of the balancing loop, or invest in long-term capacity might be viable strategies.

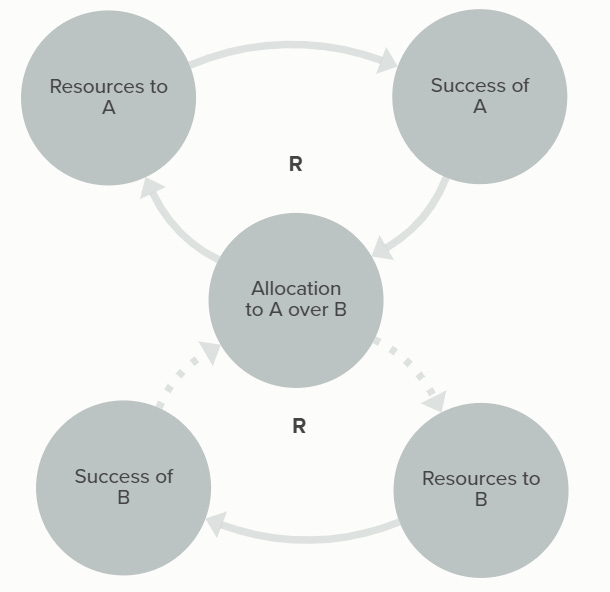

Success to the Successful

This archetype is also popularly called the Matthew effect1, based on its resemblance to sayings of Jesus along the lines of “to those who have, more will be given; from those that lack, will be taken away what little they have”. The key is that there’s some allocation mechanism that determines the distribution of a finite pool of resources, making it a zero-sum game, where the resources directly contribute to future success. This means that small differences in initial success tend to be amplified/reinforced over time for reasons that have nothing to do with potential, merit, etc, making a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy that justifies the original allocation decisions.

All manner of policies can be applied to adjust the allocation rule to soften or eliminate this effect: progressive taxation, affirmative action in college admissions, salary caps and draft rules in sports, etc. All of these essentially seek to reverse or counteract the direction of the flows coming out of the allocation decision, moving the loops more toward balancing.

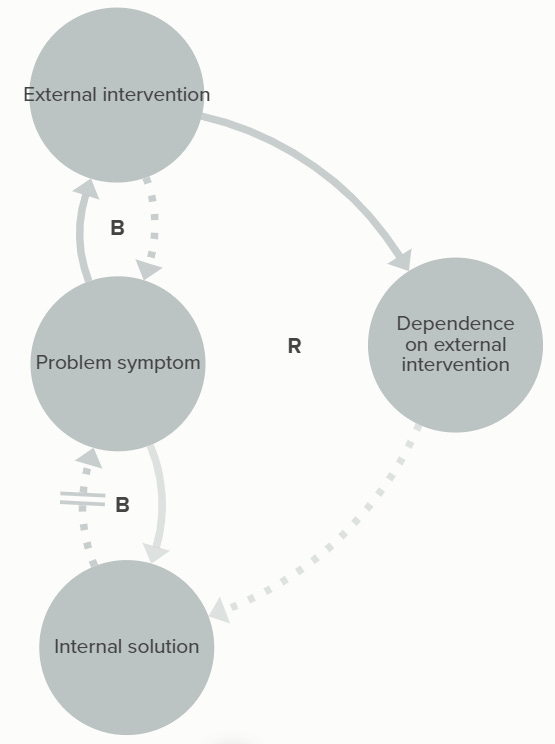

Shifting the Burden

This archetype is also often linked to addiction, and it’s easy to see why: for a given problem and its associated symptoms, there’s a more fundamental solution to the problem that takes time, and there’s also the possibility of taking a different action that will alleviate the symptoms faster, but with the side effect of deterring or undermining the effectiveness of the real solution.

Outside of an addiction framework, this could happen when a problem in one part of the organization could be solved by passing the problem to a different part of the organization. For example, imagine that the people working the front desk at a clinic don’t consistently collect copays. Retraining and holding them accountable would take time and effort, but normalizing the shifting of the responsibility to the billing folks (to try to collect after the fact) creates additional administrative costs and lowers the collection rate; in the long run, it may also assure front desk staff that their collection efforts don’t matter, further driving down compliance. Looking for solutions that solve the problem for the whole system, paying careful attention to possible side effects, requires additional thought and coordination but can break dysfunctional cycles.

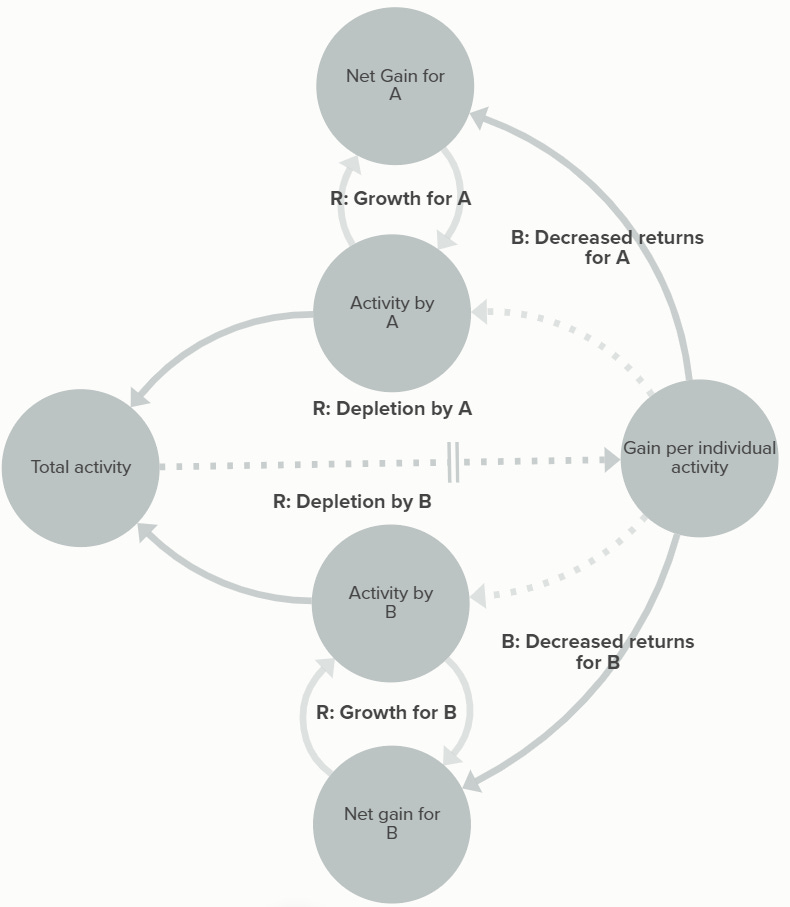

Tragedy of the Commons

This is the most visually-complicated archetype, but fortunately it’s well-established as a concept in economics and environmental science2: some limited common resource becomes over-used because of the totally rational response of each individual actor3. For the individual user, increased use of the resource (grazing land, fishery, social trust) allows growth, but the increased use also depletes the resource for everyone, which speeds up the depletion while reducing returns for everyone. Sometimes these systems can compound: ahi tuna is threatened by overfishing, but also, the awareness that ahi may not be plentiful in the future makes me want to go eat poke as much as possible while I still can4, contributing to demand and accelerating the overfishing.

The solution to a system like this always lies in coordinating efforts beyond the level of the individual. Some kind of coordination to ensure the overall sustainability of the system is needed: cartels, carbon cap-and-trade, per-use tax to soften the growth loops, etc.

OK that’s all for the systems archetypes and for the first half of Systems Thinking. When I return after spring break, look forward to chaos, complexity, and a more explicit tie-in to Futures.

Most prominently in Chapter 1 of Malcolm Gladwell’s pop-science book Outliers, where he uses it to describe the way that youth sports leagues give the most attention and play time to the most promising players (often the ones who happen to be on the older end of the cohort).

Though, as with many of the intellectual advances of the 20th century, it comes with a pedigree rich in eugenics.

There are two actors in this diagram for simplicity, but the mechanisms get stronger the more actors participate.

Am I the only one?