Understanding change is a critical component of futures studies: if the future were the same as the present, there would be nothing to study. I will refrain from mentioning any number of business and pop-wisdom quotes about change being a constant part of life. As an American born in the mid-80s, the years in the mid-90s when I came of age certainly seemed like a time of incredible stability1, but even I felt the change of the early internet2 and the end of neon. This week we focused on theories of change: how to describe change, where changes come from, what patterns they follow, etc.

One useful distinction is to describe change as either continuity (a trend continuing) or novelty (a discontinuity where the future is fundamentally different from the past). Some of this is a matter of degree/perspective - generative text AI has been improving continuously over the last decade or more, but is now at the point where street-level tech can convincingly replace some human work, and the world suddenly seems changed.

A classic treatment of the problem of the nature of change is the Molitor model describing patterns of change. This is the most pragmatic and comprehensive thing I’ve ever read on why things change in human societies3. Graham Molitor describes the places to look for early signs of potential change and the shape that the change is likely to take. The paper describes 9 patterns. For example, if you want to scan literature for change, you’ll see ideas first in art and poetry, then in science fiction, then fringe media and unpublished speeches, then technical journals, then pop-science magazines, then intellectual magazines, then middle-brow magazines like Time, then public opinion polls and government reports, then books (maybe especially “airport books”), then newspapers and TV, to the point where the trend dies down and is finally covered in history books. If you want to scan geographically for change, look at what’s happening at Berkeley, then New York and LA, then on to Boston, Chicago, Philly, Portland/Seattle, and then to the rest of the country. The overall soundness but also the datedness of both of these (the process started in the 50s, as I understand it) made me wonder about two things not covered: how do these processes of change, themselves, structurally change4, and what is the “sieve” that determines which changes continue through the process and which never get past the early stages? Some of the answer seems intuitive, like how social audio (Clubhouse, etc) was a fundamentally dumb idea, and the world is chaotic enough that I’m not expecting perfect prediction, but that’s where my head went next.

Several of Molitor’s “patterns” relate less to the discerning of early signals of change and more directly relate to watching the change work itself through society. I found this Atlantic article a fascinating companion piece to this idea. Once a (physical or social) technology is invented, it needs to be scaled, deployed and implemented, and all of these are skills that can develop or atrophy in a society over time. In the article, Derek Thompson points out the historical trends over the last 50 years that have made it so hard for Americans to do basic things like provide energy or transportation or even housing infrastructure for our growing population, most fundamentally a decrease in the trust and trustworthiness of government as a partner in solving important problems.

One of the key schools of futures studies is the Manoa School, based on the work and intellectual legacy of Jim Dator, who founded the program at the University of Hawaii. Dator’s main contention about change was that, rather than being driven by the values and desires of society, our values and beliefs are driven by our behaviors (we adopt values and beliefs to explain and understand our behaviors), which are driven by our technology5. Thus, social change is fundamentally driven by technological change: for example, the sexual revolution was driven less by changing ideals and more by things like the birth control pill, penicillin, and the Supreme Court decisions overturning obscenity laws, which by changing behavior changed beliefs. This sounds pretty reasonable to me if I squint, but when I think too hard about technology defined broadly as “how humans do things” it starts to sound tautological - of course technology drives behavior, because it’s been defined as the means of behavior - the set of technologies available define the range of possible behaviors, but then doesn’t adoption or failure of technologies represent values-driven judgments on which technologies we want shaping us?

We were told that this paper, and Richard Slaughter’s work more generally, is representative of the Australian School, another strain of futures thinking. The paper’s framework grows out of the observation that speculation, foresight, planning, and choosing is a fundamental part of the human experience. Thus, change is something we’re constantly imagining, and then we’re taking action based on what we imagine, so how can we imagine the kinds of things that will help us create the futures we really want? Societies become healthier, then, as we learn to do this work at bigger and bigger scales in society. This mind-centered theory of change6 is carried to its logical conclusion: if our outcomes improve as we move to think about the future with a larger collective mind, then not only would the greatest good come from all of humanity having an experience of the oneness of all things, but this event is presented as modern eschatology, the prophecy of the Heavenly City for people too smart to believe in religion.

All this ties back to the Polak Game exercise from the first week, where we had to think about how much we thought the future was within our control vs controlled by outside forces. None of these three approaches (mapping the course of events as laws, reducing to technology, or reducing to mind) is particularly satisfying to me. Although I find myself tempted to find a brilliant solution to this problem before I’m halfway through my first class, I’m wise enough to instead sit with the tension for a while longer.

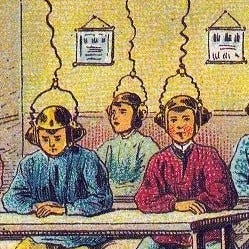

BONUS CONTENT: this CBS News special from 1967 called The Futurists was referenced in class, and I took the time to watch the whole thing. It’s a set of interviews with early futurists about what life would be like around the year 2000. There were some things that are definitely biases of the times, such as overestimating the future importance of Japan and underestimating China, but generally the things that people were thinking about at the time were reasonable: clean energy through fusion and battery technology, conflict between the global North and South, the global spread of medicine and public health initiatives, etc. The one exception was R. Buckminster Fuller, who sounds like he’s from another planet, talking about atomic teleportation of people, extensive moon bases, and all production being automated so people are only useful as consumers.

This era even fooled certified grown-ups like Francis Fukuyama into thinking we had reached the end of history.

Highlights included message boards, hand-curated directories of the best new websites, and the dancing hamsters.

Second place goes to Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel, but that doesn’t have much to say about the future or about things below a civilizational scale.

For example, how do various forms of online media find the right “slot” in the progression, or why is Portland now obviously cooler than Philadelphia and New Jersey

Again, technology broadly defined to include not only smartphones and emojis but also democracy, the nuclear family, etc.

As opposed to Molitor’s event-centered theory or Dator’s technology-centered theory.