Futures takes lots of words with loose definitions in common parlance, and uses them with a specific meaning: scenarios, signals, scanning, etc. Because of this, I want to start the discussion about trends with a precise definition: a trend is a measurement of change over time.

Fundamentally, a trend isn’t about the future at all: current trends are a measurement (quantity vs time) of some change between the present and one or more points in the past. However, talking about likely futures requires talking about trends, because these tend to persist in the short run without a dramatic shock (or, from a different perspective, the cessation of the trend would itself be a dramatic shock).

So what can we say intelligently about whether trends will persist, reverse, etc? A good place to start is the Molitor model of change I discussed in week 5. Trends have a common shape (the S curve of emerging, adoption, saturation, and perhaps dying off), as well as taking common paths through society1. The precursors of trends are the weak or strong signals mentioned in week 72, but a real trend is something actually happening rather than being speculated. For example, people driving electric cars is a trend, getting around in flying cars (though closer than ever!) is not. This stage, when the trend is playing out in a non-trivial way, is exciting because it’s where the interesting impacts and second-order effects start to manifest; to continue the example, as electric cars have become mainstream (though still a very small percentage), the temporal pattern of electricity use is starting to change, cities are thinking differently about how to raise tax revenue to pay for roads, etc.

Spotting, explaining, and illuminating trends is the most fundamental activity of foresight. Starting with a strong continuity baseline gives us something to compare other possible futures to. So how does somebody effectively identify trends? Short of doing original measurement and research, the key is knowing where to look. Governments, NGOs, and businesses regularly publish on trends that are relevant within their sphere, and they underlie lots of journalism in mainstream media as well3.

The work of trendspotting happens within a particular context, not only a cultural and socioeconomic context but also with particular organizational incentives, outlooks, taboos, etc. Thus, by examining a trend report we can learn a lot about the contours of the organization that sponsored it. In addition, specific reports might favor different methods of identifying trends and communicating their vision. For example:

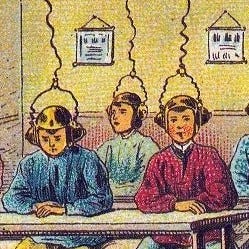

This report of 50 key trends to watch, from the Dubai Future Foundation, uses big, clean images and lots of white space to reinforce its “imagine a world where…” vibe. It explicitly focuses on growth, prosperity, and well-being, and assumes that technological progress will, despite some side effects, bring a future with much more of all three of these, rather than things like massive political unrest. It has megatrends that it organizes these under, and found the issues through scanning, interviews, and focus groups. It serves as a great example of the kind of clean, shiny, orderly future that countries such as UAE and Saudi Arabia are competing to be seen as leaders of4.

This report on the future of transportation in Asia, from Arup for the Asian Development Bank, seems to have gathered its elements through a STEEP-style analysis (discussed in week 6), and focusing on communicating/persuading through charts. The focus is on solving problems through investment in infrastructure and technology, exactly the kinds of things that you might need a development bank to help with.

This report of relevant trends from the GAO exists to provide context for lawmakers and policymakers, and so it serves mainly as an enumeration of threats and problems rather than a broader view of possibilities, and carefully words issues in the kind of forced neutrality that ensures bipartisan palatability5.

None of these issues of motive or parochialism stop these from being good and useful views of trends, but it points to what might be left out or what additional perspectives might create a balanced view.

Molitor’s paths include sources (from patents to trade publications to regular newspapers) and geographies (LA to New York to Seattle to Philadelphia to Peoria).

In some ways, a trend is like a curve connecting multiple points, whereas a signal is just a single point. This also suggests the danger involved in blindly extrapolating trends.

Though often not the front page, which tends to be driven by surprising events.

For examples of the Saudi side of this, see the Muqaab and the glowing world orb.

As one example, only Republicans are resisting raising the debt ceiling, but the report talks vaguely about “[q]uestions over whether the debt limit will be raised or suspended”.