Once scenarios have been created and communicated, your audience has the necessary materials for thinking about some possible futures and how wide open the set of plausible futures really is. This represents a huge amount of work, but is just the prerequisite for true strategic foresight. In the Framework Foresight conceptual model, we’ve finished the Mapping half of futures work (describing/imagining what may be) and are now ready to begin the Influencing work of planning for and changing the organization’s future course.

Visioning

Effectively using scenarios requires an organization to have a clear understanding of its own underlying purpose. The first step maps closely to what companies and non-profits traditionally refer to as their big-v Vision, which is a (usually vague) description of the world they are trying to create1 — for example, Oxfam International: “Towards a just and sustainable world”; Nike: “to do everything possible to expand human potential”; Providence Health: “Health for a Better World”.

A vision can also be constructed using visioning methods in foresight that more explicitly reference a potential future. This is often called the “preferred future”, but this still confuses me: for all but the most dominant organizations, the future is more or less exogenous, and our purpose in building strategy is to navigate through that fixed environment - “surfing the tsunami”, as Jim Dator puts it. Your ideal future doesn’t come packaged with the tools to bring it into being, so the act of imagining alternative futures and the vision work of deciding how best to live your values in whatever future arises strike me as distinct; I’ll have to spend more time on this2.

Implications

Imagining alternative scenarios is useful because the actual unfolding of the future changes the ideal strategy, and the first step is to tie the scenarios (each representing a possible external state of affairs) to their relevance for the business. One important technique for this is the generation of implications. By working from the general milieu of a scenario to a set of concrete possible outcomes, the strategic implications become much more obvious.

One simple way to generate implications is by using a futures wheel3. This is basically a mind map adapted to futures work, where instead of subordinate ideas radiating from a main concept, we have consequences: events or outcomes that could emanate from the more central idea. Because of this structure, items that are further out are both farther into the future and less likely to occur than their predecessors.

Specifically, implications can be formed by choosing, in turn, a scenario of interest, a desired level of analysis (global, national, organizational, etc), and category of interest from the domain map, and then identify a key change in that category that occurs in the future outlined by that scenario. Then identify potential downstream events by repeatedly answering the question “what might happen as a result?”, creating a branching directed graph of possibilities. Do at least three generations of this to get to some really provocative events (but don’t stop at three if things are getting interesting). Some of these will have an “if you give a mouse a cookie” vibe, but that’s fine - just let the ideas flow and branch out as they come4. Three specific tips for this work: finish one generation before moving on to another (all first-order effects before moving on to second-order effects, etc)5; don’t skip steps in a chain of causation; and try to generate a mix of positive vs negative, obvious vs outlandish, etc.

This process, repeated several times, will generate a huge number of potential implications to discuss: for example, if AI companions become commonplace, more people might choose to avoid romantic relationships with other humans, which might lead to a decline in the birth rate, which might put strain on social welfare funding; it might also lead to an increase in the ability for people to take the next step on idle ideas they have, which might lead to an increase in startups, which might create demand for an alternative to employer-centric health insurance. Filter this set by what’s most salient to the audience, making sure to keep a healthy mix of “no-brainer” implications (important and high probability, probably close to the center of the wheel) and “big if true”, provocative implications (high impact events toward the outside of the wheel).

Bonus Content: Dator’s Four Futures

This week I did one of the student presentations; my topic was the four future archetypes from the Manoa School. I have written about this in the past, but I wanted to dig deeper to understand their motivation, and to think deeply about how those archetypes compare to the set used by the Houston program, which are derived from them. You can look at my slides if you’re interested6, but a few things stood out:

I think Houston’s Baseline future has a big advantage over the Growth scenario: often the future has been less cyberpunk and more like r/ABoringDystopia: what if we developed incredibly advanced technology and then used it to better target advertisements? The last slide, with video ads in urinals, is pointing toward this.

The Discipline archetype still bugs me, because there’s a world of difference between a world where discipline is because of people internally committing to a set of values, and one where those values are imposed by an authoritarian government. There’s a gradation of possibilities in between, but the worlds feel as different as solarpunk and grimdark YA dystopia.

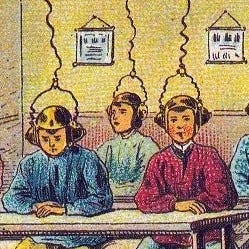

If you haven’t used it yet, try DALL-E 3 via Bing. I used Dator’s descriptions of each archetype as part of the prompt to generate the images accompanying each; giving lots of detail gives the AI more to work with (though it may not capture everything). It’s ideal for a picture to capture a vibe, as in this presentation. It’s also great when you have a visual metaphor, like making a wave out of hands to show how the evidence Dator presents is kind of hand-wavey7.

To be sure, many organizations do a bad job of this, with a vision that is either focused on themselves or on immediate business metrics, such as McDonald’s: “to move with velocity to drive profitable growth and become an even better McDonald’s, serving more customers delicious food each day around the world”.

Next semester it looks like I’ll be taking Systems Thinking with Wendy Schultz, who wrote her dissertation partially on visioning methods in futures, so if I don’t have a good answer by then I’ll know who to ask.

This is usually called the Futures Wheel, but the method is so simple and generic that I really struggle with capitalization and definite article use. I covered this in Intro as well, but I like my description here better.

Filter at a later stage by trimming events that fall outside the timeframe identified in your scope, or that are too far beyond plausible for your audience.

This is to make sure you really squeeze out an interesting set of possibilities beyond just the obvious.

This is probably obvious if you look, but I never think about slides as self-contained; they’re always a visual accompaniment to my presentation. This is frequently a poor fit in the corporate world, where slide decks are supposed to fully encapsulate your thoughts and arguments, but I decided to pretentiously buck the system many years ago and it’s too late to back down now.

Sincerely, it must be nice to be such a legend in an academic field that you can just write things down and have them be self-justifying.