Reporting the Future

Because futures work is about helping people imagine possible futures that don't exist yet, much of the success of a futures project will depend on how well the results are communicated. At best, a successful project not only improves strategic decision-making in the near term but leads the organization to invest in a long-term strategic foresight capability; at worst, the scenarios are put on a shelf and ignored. Deficiencies in soft skills like clear writing, graphic design, and visual storytelling can seriously limit the impact of even the most meticulously researched and creatively designed futures project.

As an example of great communication, consider this 2014 futures project prepared by the Houston program for the Lumina Foundation. In 174 pages, it clearly lays out the various artifacts that were created along the way: the domain map, current assessment, an overview of scan results, comprehensive explanation of baseline and alternative scenarios1, and the strategic implications. It’s clean and professional, with a mix of main text, callout text, and diagrams.

Compare that to this 2017 white paper developed for NASA about the future of work for their Langley Research Center in Virginia. The futures work here is perfectly good - it is significantly shorter than the report for Lumina2, but includes an interesting section laying out a phased strategy incorporating ideas from three of the scenarios and hedging against the fourth3. It doesn’t have quite the same level of polish as the Lumina project, and it’s instructive to consider the small touches that make the Lumina report “pop” a little more: logo; use of color in text and figures; font choice as well as use of uppercase, bold, and italics; tables having crisp headers; line weight; section dividers. Developing an eye for these details as a creator is a soft skill not directly related to Futures competency, but essential to allow the work to reach its potential without distraction.

Personas

One method used in the Lumina report above that’s not part of the standard methodology is the development of personas. This is the segmentation of a population in question into clusters represented by archetypal individuals, and then using the archetypes to reveal insights about how the values and behavior of the groups will differ. One benefit of this exercise is that it gives conceptual anchors to talk about how a strategy might affect different people differently4. This is pretty common corporate exercise for understanding different segments of customers; for Lumina, it was four different types of college students (traditional, first generation, adult, and independent). These can explicitly be about personas in the future - for near-term examples, see: this list of three tribes of orientations to work and consumption in 2022 (from 2020); this list of four types of 2025 customers (from 2023); or this 2020 explanation of how members of four segments at the beginning of COVID might sort into five different post-pandemic groups5.

Other Formats

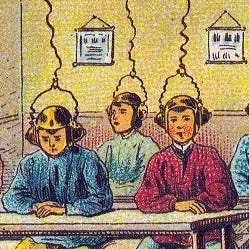

Text isn’t the only format for communicating futures, though it’s great at communicating with precision. People have spent over a century refining film as a medium for communicating ideas and emotion via the visual center of the brain, making video another natural choice. Of course, film production is its own set of skills, it creates a very linear experience, and doing it well can be very expensive6, but done right it’s a great way to viscerally make the familiar strange, and the strange familiar7. Obviously some science fiction movies can accomplish this, though many are either just fantasy spectacle or allegories for today’s political issues. Black Mirror is a good example in the public consciousness, though relentlessly dystopian. For a more benign example that only loses plausibility at the end, consider the short film “Sight”, a student project from Eran May-Raz and Daniel Lazo: it shows how persistent immersive AR gamifies the world, considers what uses of this technology would be socially acceptable, and raises questions about the level of surveillance the technology enables/requires. For a classic example, consider Apple’s Knowledge Navigator video from 1987: it anticipates the possibility of tablets, networked scholarly information, video chats, folding screens, and AI assistants8, and how their combination could completely change the way collaborative research is done.

If film isn’t your thing, what about community theater? In 2006, Stuart Candy led a project exposing over 500 community members to potential futures for Hawaii (using, naturally, Jim Dator’s archetypes) by creating four immersive experiences in separate hotel ballrooms. Led by actors playing roles from these alternate versions of 2050, participants experienced a 20-minute campaign debate, citizenship induction, community meeting, or product demo that gave them a taste of the internal logic and driving factors that animate the scenarios.

There are myriad other media that could be used to communicate future possibilities, some of which I’ve discussed in the past: future artifacts, collage, physical or digital games, AR overlays, podcasts, etc. Exposure to good work can help develop a sense of what medium might work well for a specific project and audience. Being willing to be bad at first (aka practice) can help you develop a broader set of skills.

Bonus Content: Ethnographic Experiential Futures

We had a neat student presentation this week about the intersection of two branches of the field: ethnographic futures, which extracts the images of the future that already exist and are floating around society; and experiential futures, where people have multisensory, interactive, often unscripted experiences with ideas, possibilities, and objects from potential futures. Standing at the nexus are Stuart Candy (of course) and Kelly Kornet, who write about several projects they’ve conducted along these lines, many of which fall under the umbrella of “guerilla futures” where futures content is put into the wild and you see what happens (rather than a formal, structured process). They document some of these efforts in a great blog post that demonstrates that there’s not a right order to these two elements: in one project, future artifacts were placed in Honolulu and reactions were observed; in another, people were given a phone number to call and describe their “future dream”, an artifact is built that represents that dream in some way, the artifact is sent to the person, and the person reacts/responds over the internet. This kind of futures work is fascinating to me because it’s so far out of my comfort zone. It makes lots of sense for community efforts, and I wonder if it also could be helpful as part of a large organizational futures effort, to test and refine whether future possibilities and scenarios developed by senior leaders will resonate throughout the organization.

The futures look very different from those dictated by the Houston Method: rather than having all the drivers shaped by the four archetypes, each of the 6 domains of the topic (Living, Learning, Working, Playing, Connecting, and Participating) is examined separately a baseline and alternative are created based on trends breaking, plans not being realized, and surprising events occurring. This was partly because this study was done 9 years ago when Framework Foresight wasn’t as structured, and partly because the breakdown of the effort into 6 domain-specific teams led to siloed expertise.

Due both to doing four scenarios instead of 12 quasi-scenarios, and skipping a detailed background assessment (this may be appropriate since the project is about use of an internal facility).

One interesting feature of the NASA scenarios is that they use a huge number of drivers (19). Because this is way too many to include in any narrative, each scenario includes an assessment of which drivers are core to the scenario, secondary in importance, or neither; this classification drives which merit inclusion in the narrative.

The flip side of this is that it risks inappropriately pigeonholing, stereotyping, or otherwise providing unrealistic and unhelpful simplification of a population.

Note that none of these are great examples of using foresight to imagine the medium- or long-term future, but to imagine changes from current (Horizon 1) forces.

At least for the next few years, until AI video production catches up to where image creation got to this month.

I think this semi-quote comes from anthropology, but doesn’t have a very clear origin.

The earliest of these technologies hit the mass market within a couple of years after the demo video was released in 1987, and at 35+ years we’re just getting to the last of these.