Over the past week I’ve been playing a board game that’s received a fair amount of attention in the “games x futures” sub-subculture I gravitate to. The game is Daybreak, co-designed by Matt Leacock of Pandemic fame, cooperative for 1-4 players, and it’s about what the world needs to do to stop climate change. The game has so much going for it - it’s beautiful, it’s hard, and it is one of the purest/cleverest expressions of a theme I’ve ever seen. I think it might also be fun, but I’ll get back to this.

First off, in keeping with the theme and brand, the game has made some environmental commitments in its production: no plastics (naturally), no textiles (due to harmful ag practices in their production), and all wood FSC certified (which probably means something, but you never know). This doesn’t result in an inferior product: the wood, punchboard, and cards are really high quality and look great on the table. It doesn’t seem sustainability was as central to the ethos as it was to Earthborne Rangers, but it’s definitely part of the story. I did my part for sustainability by renting the game instead of buying it1, so any other Portlanders can check it out later today at Puddletown2 .

Here are the basics of the game. Players take the role of various global actors (the US, Europe, China, or the Majority World3) trying to address climate change. The players each have their own starting profile of clean vs dirty energy and other sources of emissions, and their own set of abilities. There are global projects that the countries can work together to accomplish such as aligning tax standards globally, each country has its own set of projects (including future technologies and ideas) it can pursue and adjust throughout the game (such as restoring wetlands or working to implement a circular economy). Many of these abilities can get stronger as players commit more of their cards to them; for example, dedicating enough effort to building regulations for the circular economy can not only decrease emissions but also decrease the overall energy demand.

After all the players work to make improvements, all their carbon emissions are added up, and anything over the earth’s ability to absorb via trees, soil, wetlands, ocean, and any direct air capture players have constructed) adds to the atmosphere and heats up the planet. As the planet gets warmer, various effects (ocean acidification, desertification) get closer to tipping points that might release more carbon, reduce the effectiveness of carbon sinks, etc; it also increases the number of climate crises players have to deal with at any moment. These crises are mostly the kinds of things you would expect (storms, wildfires, social unrest), they tend to get stronger the more that temperatures have increased, and the effects can be mitigated by developing resilience in society, ecological systems, and infrastructure4. If you can get carbon emissions below what can be absorbed, you win! If you take too long, or temperatures get too high, or any player has let domestic crises spin out of control, everyone loses.

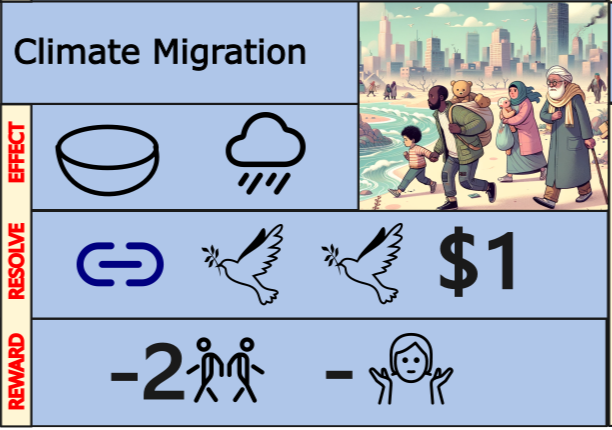

I love the design of this game. The art is evocative with consistent styles per card type. The cards are clear, and the iconography is used very effectively as a kind of pidgin language to quickly communicate effects. One of the most striking things to me is how, despite knowing almost nothing about it, the game I built last fall feels like a baby version of Daybreak: using resources to address crises before the bad effects get out of control. My favorite upgrade is that every card includes a QR code that links to a few paragraphs of explanation about the issue and links to further sources - this is so cool and I want to see it everywhere. I think everyone interested in futures and games should play this game to absorb this and the other structural lessons - it’s really a brilliant “nonfiction game5” design with a lot that can be adapted.

I have played 5 full games of Daybreak this week. In the first one, I was playing as China, and my efforts to decarbonize led to blackouts which created social unrest and then a total collapse of society, with the US looking on in horror but baffled as to how to help. The second and third game I played solo; in the former I was overwhelmed by a set of concurrent crises (air pollution, a healthcare crisis, heatwaves, and a loss of fertile land); in the latter I invested heavily in resilience to withstand the crises that came, but the rising temperatures caused too many cascading effects to decarbonize in time. The fourth game was with three players; we started really planning together but a cascading set of problems ending in water pollution pushed the Majority World over the edge. The 5th game was back to two players and we finally won! It was intensely collaborative and several things worked together in our favor: we immediately started work on decarbonization of the economy and invested in alternative energy; in this case, I (China) invested in nuclear and there was a global effort to make breakthroughs in fusion, and the US did a lot to create additional carbon sinks - planting trees, restoring wetlands, etc.

You can see from the paragraph above one of the key strengths of the game - the intense connection between mechanics and theme allows stories to emerge organically, which leads to lessons that come over time. One example: by the end of game 3 I was convinced that investing in resilience was the key to success because it helped society weather the various crises that come, but after game 5 I had decided that focusing on resilience was more of a “don’t lose” strategy, and aggressive decarbonization really needs to be the focus. The fact that I was able to acquire wisdom about the situation through play shows the power of well-designed futures games, but it also exposes the degree to which experience relies on the biases and assumptions of the designer in creating the system of the game. In the case of Daybreak, the assumptions seem reasonably well-founded: as temperatures rise, we should expect more (and more severe) crises; we should expect energy demands to continue to rise, so we need to ramp up clean energy faster than we decommission dirty energy; the non-linear nature of climate change means that problems can escalate quickly and compound6; geoengineering is a temporary fix at best and pretty risky.

One of the most subtle structural biases that guides the game is the encouragement of full player collaboration: players play their turns simultaneously, all their cards (including their “hands”) are face up on the table, and any amount of discussion can occur on the best way to work together. This level of cooperation is common in Leacock’s games, and in game terms creates the risk of “quarterbacking”: since effective cooperation is required to succeed, one player decides the right course of action and tells all the other players what they have to do to win, sucking all the fun out for everyone else as they are reduced to additional components in an elaborate solitaire game7. This game issue scales up to the real world, where global warming is seen as an issue with a “right answer” decided by elites and experts, and everyone needs to get in line with the plan or they’re committing ecocide. In fact, Andrew Navaro and I discussed this issue in January, where he specifically called out Daybreak for telling people what to think and forcing the message on players instead of letting people imagine their way to a better future8.

After all this, the question remains: is Daybreak fun, and, if not, who is it for? We enjoyed ourselves each time, though more than once it definitely felt like things were pretty hopeless. Once we got a rhythm we were able to pretty effectively discuss the best course of action, which smoothed the gameplay. However, I can’t imagine this being a game that many people would return to frequently in a casual setting. I think the absolute best-case scenario for this game is serving as the basis for a fancy high school science course or an undergraduate course on climate change. The students could start by playing a few times in different configurations, taking notes on what worked well and what didn't and the implications for climate policy and action. Then, have them research various elements of the game (projects, crises, and environmental effects) and present on them, have a robust debate on things like geo-engineering, and cap it off with a paper proposing a balanced, achievable 30-year plan to prevent the worst effects. Then the game serves as an engaging anchor and simulation throughout the course, and a way to force people to think about all the parts of the system and how they interact, rather than getting stuck on just one piece.

Paying $10 instead of $50 for a game I wasn’t sure I would keep coming back to may have also played a factor, plus the game is hard to find at the moment.

Tell Miles I sent you.

This is basically a new-ish term of art for what we used to call the Third World and often call the Developing World. I don’t love the term, as it’s not very descriptive; Global South may be my favorite of the current terms.

Developing resilience, of course, takes away from other priorities you might be pursuing.

I may have just invented this term, but basically it means a game you read about on NPR.

Humans are bad at imagining this non-linearity, so games are a great way to build intuition.

At least, that’s what the people I play with have told me…

To some extent, by focusing on national and global initiatives, the game also makes it hard for people to imagine what they can do in their own life to make a difference - either the elites will fix it or they won’t.