So far in Systems Thinking, we’ve covered very basic systems, more complicated archetypal systems, complex systems, and chaotic systems. I mentioned Stephen Lansing’s article explaining how these can be considered as different points on the spectrum of complexity1, but that’s more of a peek behind the curtain of the universe than a practical way to organize and deal with systems based on their characteristics. Today I want to talk about another approach to making sense of systems.

The unabashedly Welsh management consultant Dave Snowden used the term Cynefin to name his framework, then built an entire business around it and related methods. The concept has evolved quite a bit over the past few decades (if you’re interested in an exhaustive history, Snowden provides a seven-part serial starting with ideas about the changing cost of encoding knowledge in intermediate representations at different levels of abstraction and taking a pitstop in the middle claiming responsibility for Donald Rumsfeld’s contribution to popular philosophy), but the basic ideas are expressed by different attributes of a single diagram, which seems to almost always be drawn in an informal way.

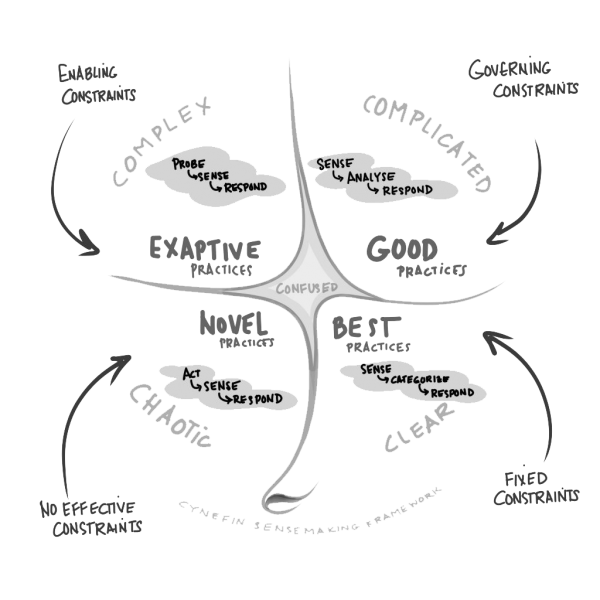

The grid divides the world into four types of systems, corresponding closely to the structure of the course: clear (essentially, simple), complicated, complex, and chaotic. There’s also a middle section labeled “confused”, for situations/problems that we don’t know enough about to classify.

The geometry of the diagram makes the adjacencies between types of systems clear, many of which I’ve discussed in prior weeks: simple loops stacked together make complicated systems, adding some intelligence into a sufficiently complicated system can create a complex adaptive system with goals adapts toward, and these complex systems pushed past their tolerances start exhibiting chaos. The fourth connection, from chaos to clear, is a good reminder that chaos was originally discovered from very simple deterministic systems, and that simple, brittle systems can easily descend into chaos.

Applying Cynefin

Preface: this is a tool built over decades that entire consulting offerings are built around, so be assured that my understanding and what I’m able to communicate are not plumbing its depths.

The map also makes clear that problems involving different kinds of systems should be solved by different strategies. For Clear systems, where we’re dealing with something common and repeatable, there’s a “right” answer, so what’s needed is to evaluate and classify the situation, and then apply the correct solution for that situation. Checklists are a typical manifestation, as are troubleshooting guides that cover common failures of devices. For Complicated systems, there are experts who have spent the time to learn the details of how the system works (car mechanics, software engineers debugging code, surgeons). The problem can be analyzed2 by the expert, a solution devised (because there’s no ready-made “correct” solution"), and then implemented. Complex systems consistently surprise us with their emergent behavior, so it’s difficult to predict what will work; your best bet is to try experiments using what you have available in new ways and see how the system responds, and do more of what’s working. Parenting is a good example of this - I find myself changing tactics all the time3 because something I thought would motivate or change behavior doesn’t work (or stops working). With Chaotic systems, the chaos usually threatens normal human functioning, so the first priority is to take steps to establish some kind of order, and then try to figure out where to go next. This will generally be authoritarian, and hopefully temporary; the Roman office of dictator is an example of building this into institutions.

There are two big ways I can see myself using Cynefin. The first is the ability to take a domain and break down problems or entities in the domain by category. As a simple example, I think about my email inbox. Lots of my emails are Clear and can be dealt with by simple rules - label spam, read news, acknowledge information4, unsubscribe from all the things that Tripp Markwell5 signed me up by accident for because his email must be very similar to mine, etc. I often do these in bulk. Emails asking questions that require more thought, or that lead me to some form or process I have to deal with, are more Complicated and require my attention to work through. Some emails are Complex; usually someone is presenting me with a problem without a straightforward solution or something broke; for example, I haven’t been paid an invoice and prior attempts to deal with it have led to more forms and bureaucracy but not a solution, and the issue isn’t being resolved. I don’t get many chaotic emails these days, where I have no idea what’s going on or how my response might make things better or worse (thank goodness), but when I do, I often need to take a walk to clear my head6.

The second approach is to chart a dynamic path through the regions. For example, the US Constitution is a complicated system (and lawyers are the relevant experts). The institutions and civil society that have grown around it to make the modern US have created a complex adaptive system. January 6th and other recent violations of civic/democratic hygiene and expectations are in danger of dragging the system into chaos7 that we increasingly lack the resources to recover from. On the other hand, the Arab Spring in the prior decade demonstrates how easy it is to shift clear but brittle systems (dictatorships with no independent civil society) into chaos, and it’s not surprising that the outcome of most was to quickly quell uprisings by a heavy authoritarian hand, rather than successfully build out the complexity required for a different system.

Just this week, complexity theory was in the (nerd) news, with Avi Wigderson winning the Turing Award for his work on randomness, computation, and complexity.

Though, of course, earlier in the semester we talked about the proximity of the idea of analysis to the reductive approach that makes it impossible to understand systems; maybe I would tweak the language for consistency, but please just roll with me here.

This is both child-by-child and day by day. When a couple is getting ready for their first child, I tell them the worst parenting advice comes from people with one kid, because they know what “kids” are like. But also, we’ve done pretty much all iterations of chore charts etc and they all stop working after a few weeks and we have to adapt. Once, when someone asked me what my parenting secret was (because my kids are usually good in public) I answered in one word: “inconsistency”.

It’s not often I praise Microsoft products for sparking joy, but the ability to react to an email with a 👍 showing that I have acknowledged receipt/understanding is pretty great.

A perfectly nice person, I’m sure.

Note that this paragraph and more personal examples for the next one could be expanded to really good chapters in the book I mentioned in a throwaway footnote two weeks ago, but which I’ve become convinced could be a million-dollar book for whoever wants to right it (Steve?).

Clearly, the events of January 6th themselves represented a brief descent into chaos, one that was resolved both by law enforcement, but more importantly by the momentum of democratic norms and traditions.