Openness, Size, Speed: Three General Patterns

The meta-conflicts shaping the future

Last semester I worked on a school project for a real client in an exciting field. But it was client work, so I can’t talk about it, so I gave myself a bunch of extra work to have something to write about each week. But! Over the course of the semester, I started seeing a few conceptual collections of future signals that transcend specific topic areas like “AI” or “climate change”, each expressed as a tension or conflict between two poles. I wanted to share these ideas with you and see what you think. If I were more ambitious / less exhausted, I’d try to turn this into a Thomas Friedman-style book and frown thoughtfully on the dust jacket. Maybe someday!

Also, I’m trying a new philosophical orientation. My futurist friend Tim says, “The universe exists. Everything else is commentary.“ That is, all our concepts, from the definition of a sandwich to what we think we mean when we talk about ourselves, are mental constructs our limited brains use to survive in a maddeningly complex world. I’m treating these ideas as useful ways to orient our brains to ripples in the manifold, rather than real laws describing real objects or tendencies, as hard as this is for me. Try them for yourself and see if they help.

open-closed

This first issue is about the disruption of the strong march toward openness in recent decades. This disruption is seen in globalization, increased transparency and information flow (and decreased valuation of privacy) from the internet, and the movement toward a liberal democracy “end of history” world.

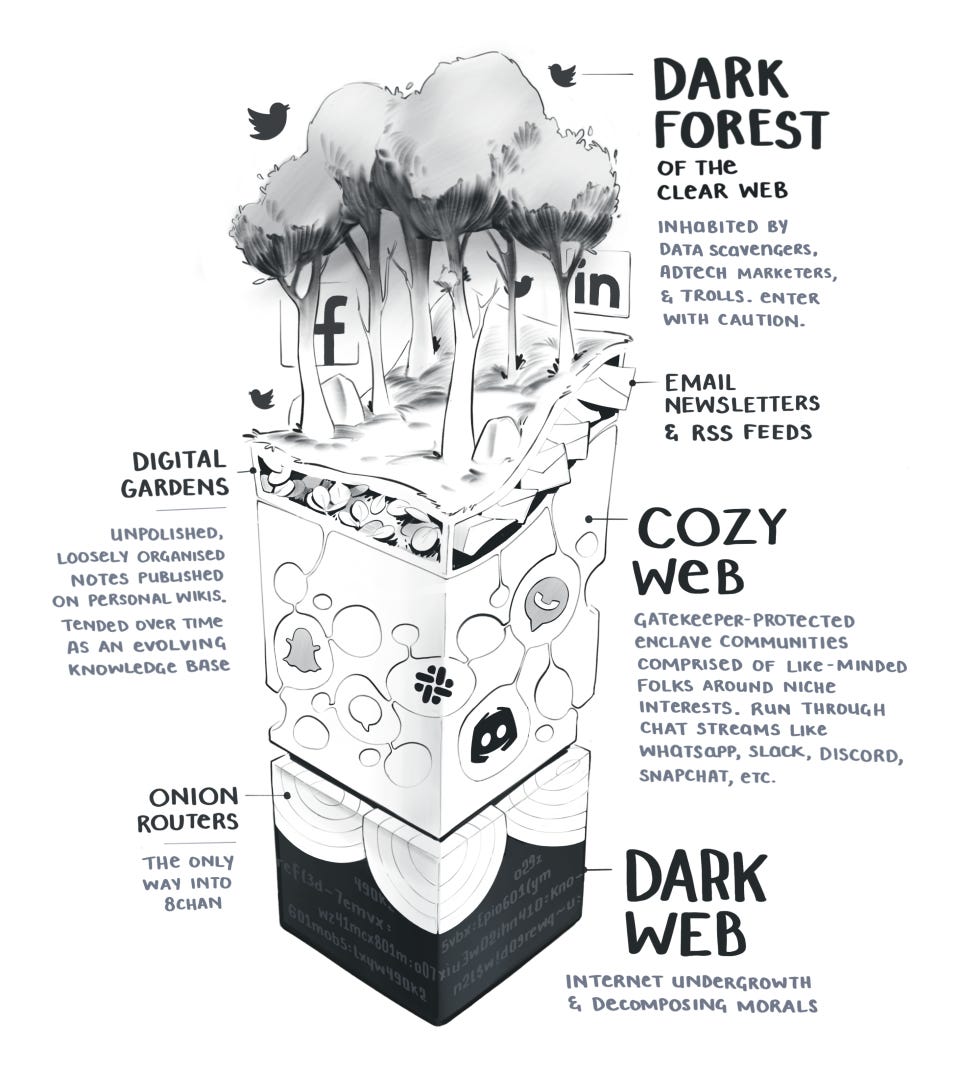

If you haven’t heard of the Dark Forest Theory of the internet, I suggest starting with the primary sources. Essentially, the idea is that the internet’s radical openness led to its co-option by advertising algorithms, loud jerks, scammers, and so on - parasites feeding on social trust and love of free things. Because of the wastelandishness of it all, people are spending more of their online time in the “cozy web” - spaces that tend to have moderation, barriers to entry, and lack of discoverability by the “free” internet. Some closing1 is the price of sanity.

Ted Gioia wrote an article about new annoyance marketing techniques. When a platform becomes so compelling that users feel forced onto it (streaming services because they have exclusive rights to content you want, Amazon because you’re addicted to next-day shipping, YouTube because that’s where your favorite content creators post, Facebook because it’s where your friends are2), the playbook is to gate that content behind more and more ads, generating revenue by getting you as close as possible to walking away in a rage before giving you the dopamine hit you came for. The enclosure of whatever good/service/experience they’re selling makes being the fence company the best play at all - it’s essentially police officers demanding bribes on the way to the market.

A major manifestation of the open/closed issue is the trend toward creating secure supply chains and/or secure lines, often at great expense. The supply chain disasters of 2020-2021 from COVID and Ever Given caused businesses to rethink reliance on global systems. Chaos at the FDA creating vacancies in food inspection teams, leading to lack of trust in supermarket greens, is a closing off at the individual level.

But open supply lines also pose risks of sabotage. When Hezbollah’s pagers and then walkie-talkies mass-detonated, manufactured abroad but apparently infiltrated by Israel, it explosively illustrated the worst-case consequence for being open. Something similar may yet happen with Chinese solar panels; bringing down the US grid on the day Taiwan is invaded would create chaos when we need coordination. But how much are we willing to pay for security, and what does it mean to trust a process and its actors? At the extreme, you have Ukraine war’s fiber optic drones, which have a literal secure line to their operators to avoid signal jamming.

In a more mundane example, many things in this world (the Google suite, ChatGPT, social media) are heavily subsidized because they collect data to enrich the product and/or sell you more things. I could see this changing; I’m surprised we haven’t developed an ecosystem of less-open paid services that adhere to a defined privacy standard, but maybe things will go this way.

big-small

I first heard of Moore’s Law of Mad Science as people were jailbreaking LLMs to get recipes for napalm and nuclear reactors: “Every eighteen months, the minimum IQ necessary to destroy the world drops by one point”. Ignore the temporal and psychometric precision here and appreciate the larger point that the arc of technological development is to make machines that do more of what people already do, faster/better/easier1, including bad things. As I mentioned last week, this often happens by making things smaller.

Murphy’s law was originally a design principle, not a pessimistic statement — if something catastrophic happens only if your product is used in a non-standard way you’re pretty sure would never happen, it will happen. Therefore, if technology advances to the point where people can use it to make big things happen, and aren’t designed carefully enough to avoid those big things being bad, you get something like Chernobyl — great television, probably not fun to live through.

We spent the last century building really big things to project power, amass fortune, etc. These include aircraft carriers, tanks, fighter jets, but also skyscrapers, robust national governments, international institutions, a global supply chain, enormous corporations, and space stations. But we are also rapidly developing capabilities that allow much smaller, cheaper tools to destroy these things for a fraction of the effort of assembling them. Some of this is certainly an old story — laser pointers vs airplanes, commercial jets vs skyscrapers, rocks vs tank gun barrels.

But lately the balance has been shifting more in favor of the small against the large. When the US Navy uses AI to auto-target lasers against potential swarms of hostile drones, a different world is emerging. In fact, a fair amount of this change is due specifically to drones: anything you dislike enough to be willing to pay a few thousand dollars to destroy is in danger.

Ted Gioia has collected signals suggesting that the interconnected system of academia, scientific research, and knowledge work system dominating society for the last 70 years is crumbling, largely due to the internet’s ability to transmit information (true or false) without gatekeepers, and AI’s ability to produce content at an unprecedented scale. Part of this is the shift in social values toward Dream Society icons eclipsing the Information Society in prominence and prestige, but also expertise is a construct requiring tall poppies, and we’ve given everyone sticks.

slow-fast

Here’s one more idea to try on. The pace of change is currently shifting in many fields. The traditional view of this is from Stewart Brand’s pace layers:

The basic idea is that the lower levels change slower, and that each level is anchored by layers beneath and invigorated by layers above. But the last couple of decades have scrambled these relations. Climate change is causing nature to change faster than culture, governance, or infrastructure can handle3. At the same time, culture has stagnated, as studios remake old movies and people listen to old songs.

Governance is an interesting case. For years, people have complained about the US government being increasingly gridlocked and unable to solve national problems. This prevents intelligent responses to crumbling infrastructure, meaningful reform of our healthcare or immigration systems, etc. However, the Trump/DOGE disruption to federal research funding and trade policy have outpaced commerce, creating massive instability. There is a “stable” level of change between “stagnant” and “sudden” that maximizes adaptation.

Wrapping Up

I love it when I can spend enough time meditating on ideas that these higher properties emerge. I hope to come back to these concepts in the future. Hopefully this gave you new perspectives on the way the world is changing. I’d love to hear your ideas, examples, refutations, or elaborations in the comments.

Note that each of these are variations on market power created by network effects - everyone is there because everyone is there.

The Light Pirate, covered two summers ago, is largely a story about nature changing faster than infrastructure, as it becomes impossible to keep electricity flowing in storm-ravaged Florida.

“… makes being the fence company the best play [of] all - it’s essentially police officers demanding bribes on the way to the market.” or governments demanding sales tax. A key difference is that sales tax and Facebook ads are legal, whereas bribes, less so.