Last week, I introduced a two-part model (with diagrams!) of what strategy is and how it relates to nearby concepts. Having laid bare my initial mental model, I will evaluate and refine it over the semester as I read and consider different viewpoints.

Early History

As part of the course, every student has to pick a strategy book in addition to the shared readings to read, summarize, and present. Much of the list seems like the standard 200-page business/airport book kind of thing, but instead I chose the 700-page Strategy: A History by Lawrence Freedman. This ponderous tome, true to its name, tracks the development of and attitudes toward strategy from primates through the sweep of recorded history. So far I've gotten through Carl von Clausewitz, and there have been some interesting connections. The pillars of strategy in warfare, back to chimpanzee society, are pretty consistent: building coalitions, deception, and using violence instrumentally1.

Traditionally, alliances and raw power are respected as virtuous, but deception/craftiness/guile has had a mixed reputation over time and cultures - appreciated by the Greeks23 and the Hebrews4, derided by the Romans and much of medieval Europe5 — plus it's the only element of the three that loses its power the more it's used, as people learn not to trust you. Sun Tzu's Art of War reflects a Taoist approach to war disconnected from this Western discourse, focusing on outsmarting the opposing force by never doing the expected, playing against the personality of opposing commanders, and finding ways to force favorable conditions.

Through the Middle Ages, battles were seen as an “enforceable wager” where parties that couldn’t settle disputes by other means could reveal God’s will based on who could take and hold the field of battle. However, by Napoleon’s time, the world had changed: the idea of the nation had taken root, logistics had improved, and maps became more accurate and detailed, so war could be more precise over longer distances, and big enough to threaten the annihilation of entire polities. This transformed strategy from a Greek loan-word describing what good generals do into a full discipline, with products and experts.

Formalizing Strategy

The most famous early strategist was Carl von Clausewitz, who aimed to provide a theoretical approach to war, unlike contemporaries like Jomini who focused on campaign planning. Clausewitz has two critical observations that transcend warfare and have passed into popular parlance. The first is that “war is politics by other means”, meaning that it is raw violence at the base, controlled by military leaders but subject to chance, serving larger political aims6. This aligns with my model of hierarchical strategy, with information coming from lower-level intelligence loops7 and constraints/objectives coming from higher levels8. Second, Clausewitz identified that any undertaking as complex as war will experience constant friction where things don’t go to plan9, and the commander that handled this friction better could make up for a disadvantage in raw numbers/firepower. For this reason, he discouraged elaborate tricks and ruses (more to go wrong), and encouraged planning and a checklist approach. This humility echoes the orientation of foresight, and especially Dator’s three laws of Futures: we can’t know the future because it doesn’t exist, useful ideas pull our assumptions into question, and expect technology changes to change not only the mechanics of war but its objectives as well.

Lastly, Clausewitz articulates something I’ve been thinking about for years, especially in the context of sports. He says:

War is not an exercise of the will directed at inanimate matter, as is the case with the mechanical arts, or at matter which is animate but passive and yielding, as is the case with the human mind and emotions in the fine arts. In war, the will is directed at an animate object that reacts.

That is, war is a perfect example where the situational environment is not inert or even changing in ways you need to react to, but actively being changed by another intelligence designed to thwart you10. Sports announcers struggle to assign agency to both sides at once: in football, if a pass into heavy coverage is caught, it’s the quarterback making a great play and trusting his receiver; if it’s knocked down or intercepted, it’s great coverage or the blitz forcing the mistake. When a new dominant strategy is created, like the NBA 3-point boom, others rush to adopt it and it stops being an advantage. This is an issue whenever the relevant players are few and powerful; game theory is likely a more useful discipline here.

Strategy Beyond War

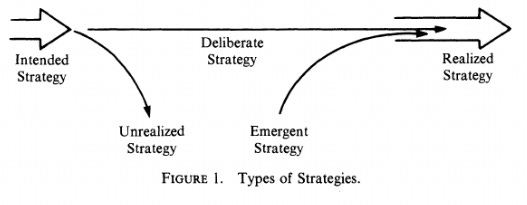

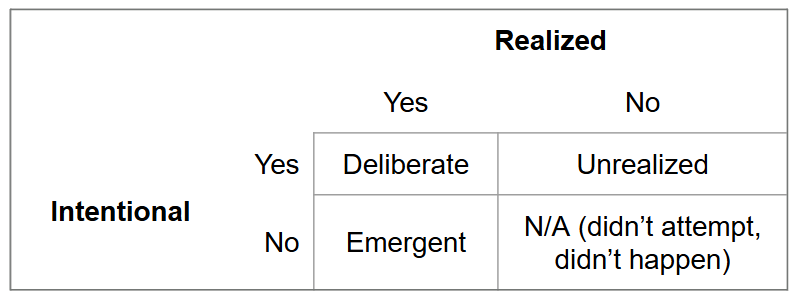

Henry Mintzberg is one of the most influential sources in strategy in organizational management (i.e., business strategy). Comparing his 1978 and 1994 articles reveals important ways both strategy and thinking about it have evolved. In the former, he defines strategy as “a pattern in a stream of decisions” (p. 935). This means an agent can have a strategy without it being intentional, similar to the concept of revealed preference in economics. He draws a potentially confusing diagram (why would a deliberate and an emergent strategy end up in almost the same place, etc.), but I think he’s just communicating a taxonomy, so I drew it in a more standard 2×2.

Mintzberg sees intentional strategy as how leadership communicates a chosen response to the environment to the bureaucracy (which seeks stability), reinforcing my conception of strategy as the plan to achieve the vision given the available information. Sometimes, it’s better not to make your strategy too clear because the “acting” parts of an organization will run with whatever you give them: if it’s too clear, it may get over-implemented. The idea of strategy including the undirected emergent kind makes sense when describing how organizations actually function11, but less so for describing the process of formation itself.

This brings us to the 1994 piece, “The Fall and Rise of Strategic Planning”. Since the 1960s, many organizations tried to instantiate the emerging field of strategy internally by creating a strategic planning function; that is, taking the end products and artifacts of strategy and creating a process to reproduce and update them, either baked into team processes or by making it the sole function of an individual or team. Mintzberg bemoans this approach, which he equates to cargo cult strategy that often impedes actual strategic thought. He talks about strategic planning as an analytical task, whereas strategic thinking is more synthetic12. Real strategic thinking is messy, pulls insights from everywhere, and can’t be forced into a set of meetings and deliverables. Rather than build machines that grind away toward sterile metrics, an organization needs to organize their strategy toward a compelling vision that people can be enrolled in and work toward in the ambiguity of their particular role. Strategic planning still has a role — it can capture, articulate, and package the strategy for distribution and management as it emerges, what Mintzberg calls “programming” (though, again, over-formalization is a risk).

The Role of Foresight

Mintzberg’s descriptions completely lack consideration or even awareness of foresight as a discipline that complements and enriches strategy development and programming. He sees the importance of sensing present realities and having a compelling vision for the future, but doesn’t connect that to a discipline that already exists13 to systematically think about how the world might change on the way to the vision, being content to leave the right half of the map blank other than the destination and hope for the best (and, presumably, frequently reassessing as the environment changes).

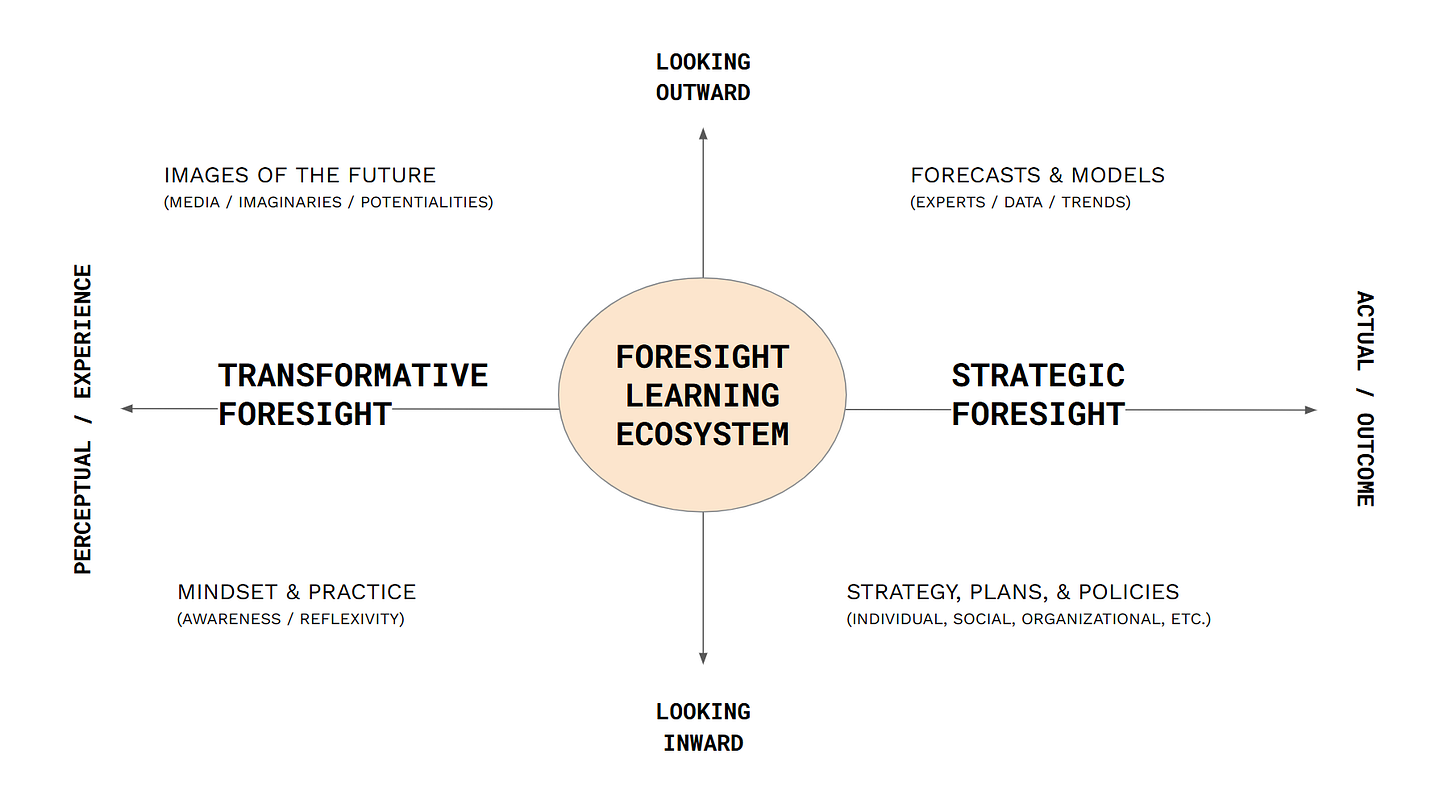

Foresight is crucial to strategy because it allows us to explicitly address our uncertainty about the future and how various possibilities would change our response, and adds to the strategic conversation in a couple of ways. This is not only through outcome-oriented foresight like identifying external trends and creating internal plans and policies, but also by the more experiential work of digesting public images of the future and cultivating a practice of increasing comfort with the uncertainties of the future. Sweeney gives this diagram to illustrate the point:

These two axes look like the foresight equivalent of Ken Wilber’s four quadrants, but another way to think about them is by the points they occupy on Donella Meadows’s spectrum of leverage points in a system. Tangible, “serious” things like trend reports and strategic options fit much more cleanly into corporate practice and are easy to digest, but are unlikely to create lasting change; changing leaders’ thinking about the future creates much deeper change but is harder to achieve or quantify. This is why it’s important to have a healthy ecosystem of foresight work in an organization across these dimensions, rather than one best or most valuable method/artifact/perspective. Between these approaches, agents can rehearse the future and prepare themselves for the deep surprises the future tends to bring, enhancing the quality and agility of strategy.

Ants, as a pre-strategic example, have war but no adaptation when things go in an unexpected direction.

Worth noting: the Greek concept of metis, or craftiness, explicitly includes foresight.

Odysseus is the avatar, counterpoint to the powerful but rash Achilles, though his reputation had waned by the time of the Peloponnesian War.

The Jacob cycle, for example, is largely about tricking and being tricked.

Machiavelli became the new stand-in for Odysseus as the stock evil schemer.

Though in any given moment, one or the other of these elements may dominate.

My model of “intelligence” as a black box needs more development; probably sensing/reacting loops need to be added.

In fact, Guibert in 1770 referred to elementary tactics (what we call tactics today) and grand tactics (strategy), and various works throughout the 1770s identified strategy as requiring high faculties of reason, which I equate to “attention” in my model.

This is his famous “fog of war” which was often literal in battles filled with cannons and musket fire.

He calls it a “contest of wills”, though “contested agency” might be more fitting today.

For example, it makes sense to talk about the unconscious losing strategies in relationships as a way of seeing these behaviors in a new light.

This mirrors Ackoff talking about the analytic urge of the Enlightenment vs the holism of the emerging systems approach, but also mirrors the Clausewitz/Jomini divide above.

The Houston program, for example, was established four years before his 1978 article.