Finally, we have come to what is probably the most distinctive and widespread work product of the futures field - scenarios. Scenarios help push people to think about the future in a new way, and can surface issues that teach us more about our assumptions and options.

Again, starting with definitions: what makes up a scenario? There’s some lack of precision in the field, not surprising for such a soft science with a strong focus on practice, but people who say that there’s no single definition what scenarios mean in the futures world are like people who say you can’t trust the weather forecast because it’s sometimes wrong, or you can’t say Shake Shack is bad because people have different opinions on whether salty mayonnaise is a reasonable secret sauce: perhaps correct in the most literal sense, but missing the usefulness of what is being offered. Spaniol and Rowland hunted through the literature for all attempts at definition and found six characteristics on which there’s pretty broad agreement: scenarios are future-oriented narratives that describe plausible (or maybe just coherent) possible futures describing the world outside the control of the entity they are designed for1, and they are packaged as a systematic group that reflects a range of possibilities.

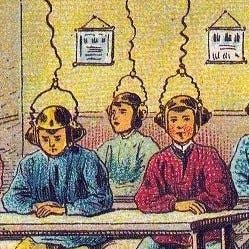

Spaniol and Rowland also point out that the word “scenario” itself, interestingly, comes from theater, and refers to the superset of a performance: that is, not just what the audience experiences, but a guide to all the things that need to happen to create that experience, including effects, transitions, etc. This points to a difference between professional foresight and what some in the field call “charlatan futurists” - if done properly, a set of scenarios should be able to show the homework of the issues and drivers that underlay them, and the process that was used to generate them, instead of just being interesting provocations about the future.

The standard model for building scenarios is called Intuitive Logics (IL). This originated in the mid-20th century from a corporate (especially Shell Oil) and US military planning context2. The first step is to scope the work, including understanding the client’s need and then negotiating the time horizon (almost all organizations are overly focused on the short term, and so the challenge will be to advocate for a longer horizon than the standard 3-5 years). Second, identify the relevant driving forces, and rate them according to how uncertain their direction is over the time horizon in question, and how big the impact is expected to be. Third, take the two drivers with the most impact and uncertainty3, create a scale for each from one possible extreme to the other, and use the two scales to create a 2x2 matrix; each of the quadrants of this matrix will need a catchy name that reflects the collision of events it represents. Next, write a narrative to serve as a scenario for each of the quadrants, explaining what events might cause it to emerge (making sure to include any high-impact, low-uncertainty drivers as part of the background of each of the scenarios), and decide on the right way to present the scenarios - the right mix of media, the number and depth of questions, etc, to best suit the audience. Again, like the negotiation of the time horizon, the goal with this work should be to stretch the thinking of the organization as much as possible without breaking it.

Often one of these four scenarios will be a consensus “best” scenario, and another will be the consensus “worst” scenario. Two things are important to hold onto: don’t let these narratives drift so far into utopia/dystopia that they cease to be useful, and, in fact, it might be a good idea to write the narratives for other two scenarios first to help prevent this and nail down the harder scenarios first.

The advantages of this IL process are pretty apparent - it’s a straightforward process that always leads to a set of four scenarios with a tight internal logic, with all the underlying work easily accessible. The scenarios can be built out according to a set template, or various world-building approaches can be taken to constructing them from their constituent elements. This work can be done with varying levels of participation from the client - trading the time it takes for a group to work through everything for the ownership and consensus that come with having been part of the process. The biggest things that are left out, due to the detached and exploratory nature of building up the scenarios, is a focus on explicitly designing desirable futures and then figuring out how to work toward them, and an inward examination of how the organization’s ability to perceive the future is constrained by the stories and patterns of thought it fosters4.

I’ll close with a couple of examples of scenarios constructed in this way that give an example of the range of possible output. This report from ARUP has really big and generic drivers (health of the planet, and societal conditions), and its narratives include a detailed society-level view and a human-level story for each with specific plausible future details. By contrast, this set of healthcare scenarios are based on very specific drivers (patient engagement and reimbursement models) and its narratives are pretty generic, describing how the systems work but without fluff, color, or imagined events inserted.

That is, scenarios for Verizon will pertain to the communications industry generally as well as consumer tastes; scenarios for the US military will pertain to the global security environment; and scenarios for a state university will pertain to the state funding climate, the direction of private universities, and cultural/economic factors influencing demand for education.

Andrew Curry provides a wonderful history of the technique and the alternative approaches it displaced.

Ideally these are independent from one another, so it’s easy to imagine one changing without affecting the other. It’s also great if the drivers are from different domains, like one technological and one environmental. Slightly trickier is the locus of control - for a small organization it makes sense for the drivers to be external, but for an industry leader or a country it might make more sense for one of the drivers to be something with a fair amount of internal influence to reflect the higher level of agency.

The Curry paper linked in the footnote above points to some of these inductive approaches, and future newsletters will go more in depth.