Non-Profit US Healthcare Futures, Part 2

More Reporting on a Work Futures Project

Following up on last week’s article introducing and walking through the first steps of our futures project at Providence Health, this article describes the rest of our project and lessons learned.

Step 2, Continued: Drivers

Having collected a robust set of scan hits and TIPPs, we were ready to articulate the drivers pushing, pulling, and holding back various futures. This was my favorite part of the entire process; we all met in person, and I used Airtable and then FedEx Office to have little cards printed out for each input as well as each of the trends from an ARUP report1 and also a private collection of about 200 trends2. We put all these in piles along the outer edges of a conference room, and then organized them into logical clusters capturing the big underlying forces affecting healthcare. We didn’t use all the evidence we had in the room, especially from the general-purpose sources, and there was some negotiation and debate as we reconfigured the drivers a couple of times. Things came together pretty organically, and the team definitely felt like understanding about likely futures emerged from the process. The whole thing took about half a day3, and then we named them and I collected the evidence to collate everything afterward. Here are our 11 drivers; the supporting evidence is too long to include here but is available here.

Driver 1: Neighbors in Need

Older populations, urbanization / rural decline, increased ethnic diversity, more chronic disease, and overall sicker patients. Deteriorating mental health esp among younger people.

Driver 2: House Divided

Increased inward focus in the US opens opportunities for foreign competition (supply chain and labor). Polarization: state-driven laws, city-vs-state, changes in trust for vaccines etc.

Driver 3: Renewable Human Resources

Work patterns favoring virtual, shortages (aging, burnout), more engagement/balance/purpose, continuing education/training. Wages are increasing as a result. Workforce activism is increasing (including via unions).

Driver 4: Synthetic Workforce

More care delivered with fewer humans. Physical (robots, drones, monitoring) and digital (AI etc).

Driver 5: N of 1

The basic framework of disease is changing (complaint and management to diagnostic and cure). Nanotechnology, synthetic biology, and omics will drive mechanistic medicine with the potential to dramatically improve outcomes, including for aging.

Driver 6: From Patients to Customers

Health care faster and more accessible (availability plus shift to outpatient/retail/home). Using technology to push care closer to patient and move caregivers to deliver remotely. New opportunities like concierge.

Driver 7: Honoring the Mission

Responsible and trustworthy with AI. Targeted approach to different populations to improve outcomes (race, age, and SOGI). More scrutiny on non-profits re: community benefit.

Driver 8: The Next Tech Stack

AI is becoming ubiquitous. New threats to cybersecurity. More data from more devices / interoperability. Evolving interaction (HCI).

Driver 9: Making Ends Meet

Patients can’t afford care. Continued tweaks from CMS, and patients shifting to Medicare Advantage, FFS and its lag makes it hard to pay for new care. Medical tourism, payor mix shifts to less commercial, shift in sites of care (IP to OP), supplies and pharmacy costs rising.

Driver 10: Sharing Data, Safely

Protecting patient data, opening to new data sources and innovation, risk of attacks, government response. The relative pull changes the responsibility.

Driver 11: Managing the Built Environment

Old infrastructure (facilities etc) are failing, new and uncertain requirements for new infrastructure (efficiency, smart buildings, what we need for incoming tech, air quality and other climate change resilience, seismic, siting).

Step 3: Futuring

Having developed the drivers, we used a (qualitative) cross-impact matrix to identify the relative salience and the interconnections between them. This prepared us to articulate the baseline and alternative futures. We discussed a few approaches to this work. A 2x2 approach to scenario building was rejected because there weren’t two obviously dominant drivers. We considered Causal Layered Analysis but felt it might be too difficult or unwieldy for a team developing scenarios for the first time. Which is a long way to say we decided to use the Houston archetypes, but did consider alternatives. Then we sketched out what each driver would look like under each scenario.

The values of each of the drivers under the four archetypal scenarios are available here. The emergent logics of each of the scenarios were pretty distinct:

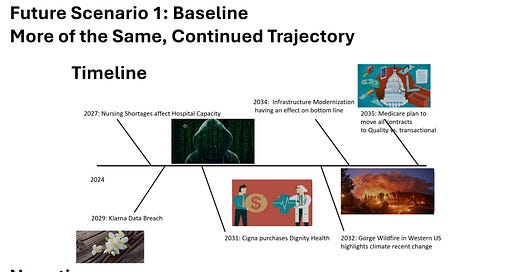

Baseline: the status quo continues with health systems limping along as demographic shifts continue increasing the need for care.

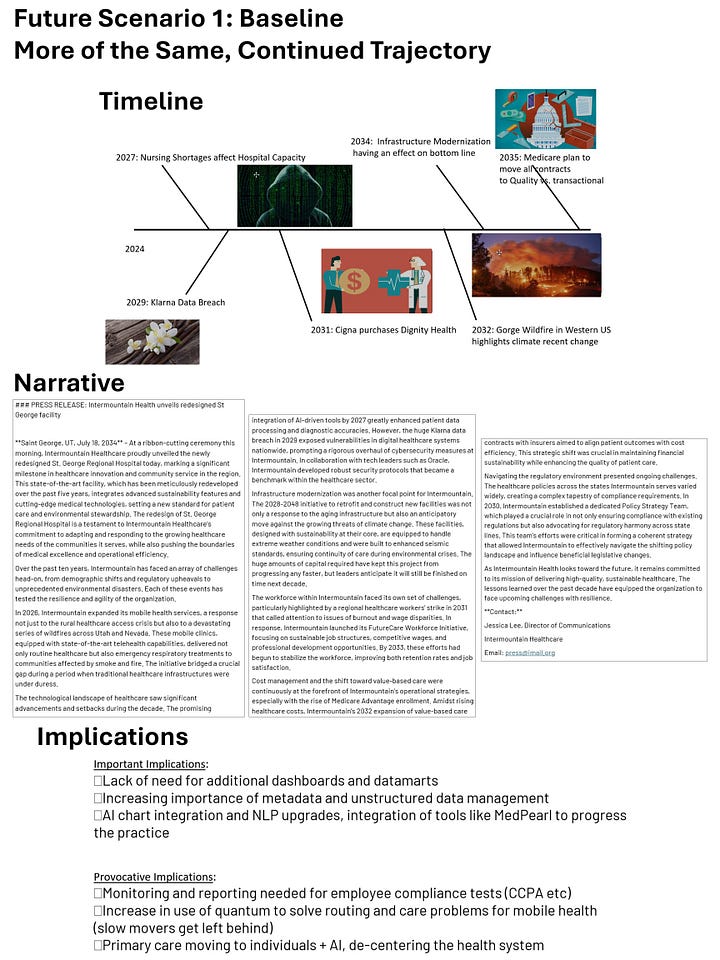

Collapse: health systems stop receiving federal payments for Medicare and Medicaid4, at the same time as something like the Change Healthcare hack stops payments for commercially-insured patients. Systems have to figure out how to survive outside the familiar payment system.

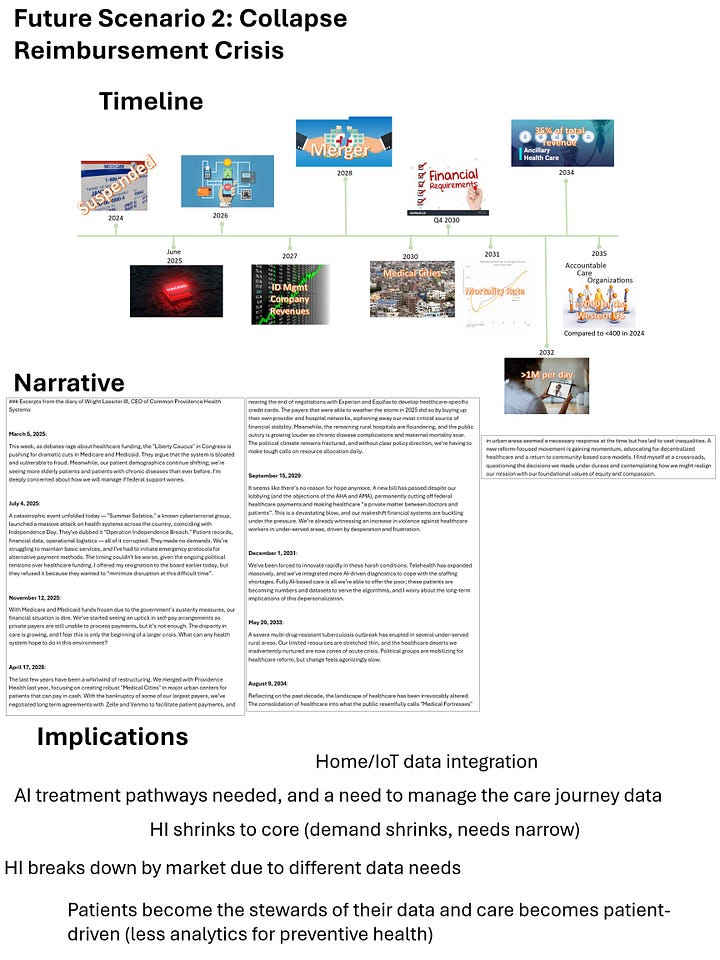

New Equilibrium: some external entrant to healthcare5 finally cracks the code and quickly grabs 30% market share, and health systems have to rapidly adapt to a new market environment to keep up.

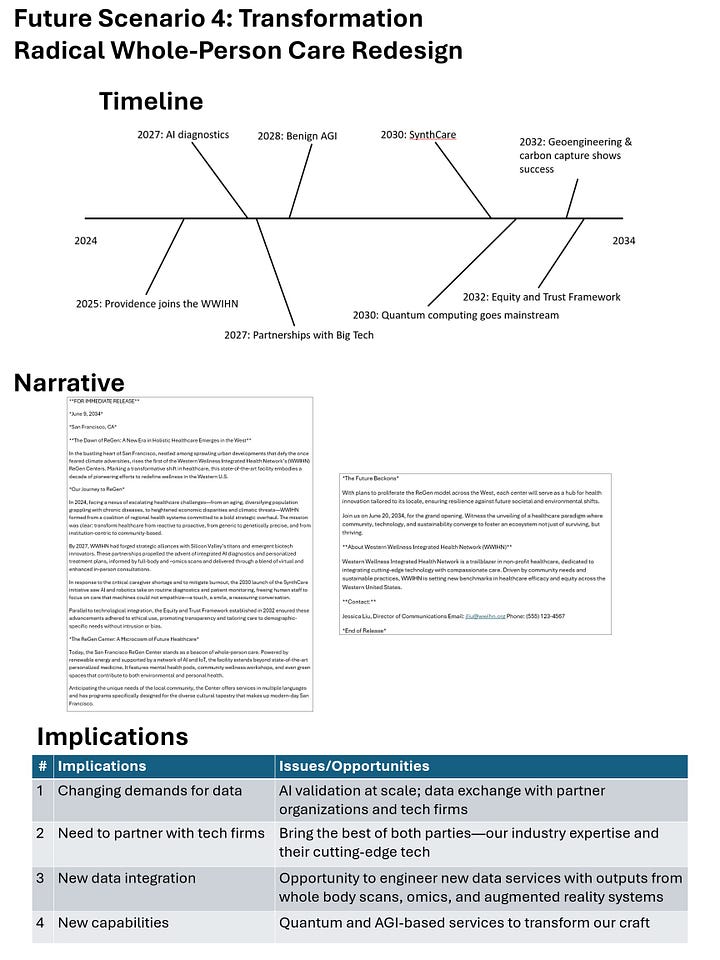

Transformation: the technical, organizational, and social pieces come together and we’re finally able to achieve integrated whole-person care.

Then, over the summer, we worked on the actual scenarios (four members of the team were responsible for one scenario each). As a starting place, we used Generative AI to create our first drafts. I’d say the AI probably saved us about half the time of development, and it made it easy to iterate: arguing with it about the logic of the scenarios made both its writing and our thinking better. Here was the prompt we used; as is often the case, the details show where the tool fails by default and needs extra cajoling:

As an expert strategic foresight professional, write me a draft of a high-quality, provocative scenario using the Houston archetypes. It should be about 500 words and use a creative framing device (press release, news story, blog post, etc). Don’t be generic – make some specific world-building decisions to make it compelling (extra points for combining drivers to reach unexpected outcomes), bring in ideas related to the signals as appropriate, and refer to real-world entities to enhance realism. It may be that some of these drivers are minor and don’t need to be referenced. Make sure it incorporates the details from the drivers, focusing especially on the “value in scenario” outcome, some plausible backcasting with intermediate events that get us from here (2024) to there (2034), and immerses readers in the imagined future world.

The project is specifically “The Future of Western US Non-Profit Health Care Systems in 2034”.

Scenario archetype: [I put the scenario archetype and the sketch of the idea here]

Here are the drivers we came up, the recent signals of change for each driver, and their values in this specific scenario:

[Each driver, description, value in the particular scenario, and the recent evidence here]

Our four scenarios are, again, too long to include in this post, but you can read them here: Baseline, Collapse, New Equilibrium, Transformation. I think the “press release” style is overdone and I prefer if only one scenario uses it, but that’s probably me being picky (I thought the journal-style collapse scenario was by far the most fun). Final note on scenarios: I recommend naming your scenarios early in this process; spending too much time calling them by their archetypes meant that people had become accustomed to those labels and didn’t want to change.

Step 4: Visioning

The next step was to use the scenarios (which exist at an industry level) to generate a big list of possible implications that might affect the client (in this case, moving from healthcare to healthcare data & analytics). This step underwent the biggest change from the original plan: originally the implications were slated to be developed in a second in-person session over two days. Scheduling was a challenge, so we decided instead to schedule four (virtual) two-hour meetings, and use one for each of the scenarios). Between the time we scheduled them and the actual dates, additional conflicts arose, so we ended up just having one session where we did a little bit of work for each scenario and I agreed to co-work with AI to fill in what was left. I regret that events turned out this way, because I learned that the divergent nature of implications make them a perfect team sport: they flow easily and are actually fun to generate in a small group, but alone they are a long and difficult slog.

We ended up doing the work in Microsoft Whiteboard, which is OK but not very good. Originally I had hoped to use Miro, which is more or less at “it just works” status. I was paranoid about the collaboration tools failing, so I scheduled a pre-meeting to test Miro vs Whiteboard. Not all team members could get into Miro6 and access a shared board, so our fate was sealed. We identified about 4 notable changes per scenario, then used a futures wheel to fan out possibilities from there, working from the industry level to things that were relevant to the department. Once all these were developed, we had a follow-up meeting to take the outer implications and place them on a 2x2 of likelihood and impact so we could identify those that are most important (high impact, high likelihood) and provocative (high impact but low likelihood). If I were doing this again, I would use the stakeholders from the current assessment as potential a lens to help generate ideas of possible implications7.

One thing we noticed was that there were some themes that showed up in the implications regardless of the scenario. Though the differences in the scenarios are what make strategic options so useful as a way to strategically manage uncertainty, these recurring issues are a sensible foundation for our efforts8. The issues were:

IoT: healthcare in the future will likely rely on more devices gathering data from patients and communicating with one another.

AI: not surprising from a futures project commissioned in Anno Domini 2024, it was hard to imagine artificial intelligence not growing in relevance and transforming the way care is delivered.

Cost/competition: much of the current focus of data collection and analysis is on treatment and billing, but the data around the cost of providing the care and around market positioning seems like it will be a bigger part of the conversation going forward.

Customer relationship management: patients are becoming increasingly mobile, and systems will need to integrate datasets to cultivate a relationship that crosses specific sites of care.

Metadata: collecting core information about our datasets, understanding business logic, etc, will become increasingly important to feed AI and other use cases.

The second part of this phase was to generate a vision for the department, so we could decide how best to respond to possible futures to build our preferred future. We knew this would have to be generated at a more inclusive level than just our little futures group, and so I baked this into our department’s annual strategic planning two-day offsite meeting, with all leadership in attendance. I took a two-hour session a week or so beforehand to orient them to all that we had built, and then we used the 45 minutes9 to walk through a discussion of how those present saw the department, its unique contributions, values, etc10. I took detailed notes of the conversation, and then over lunch I worked with AI to iterate something that resonated with people (the AI draft was OK but it kept trying to cram in extra words and ideas instead of simplifying to the bare essentials. Here’s what we landed on, which I think turned out very well and everyone seemed to like:

HI helps transform healthcare by leveraging data and AI to create intelligent, seamless solutions. We aim to integrate all types of data, automate processes, build extensible platforms, and foster strategic partnerships, making data accessible, actionable, and impactful for clinicians, researchers, and operational caregivers.

By driving insightful, data-driven decision-making, we support and enhance patient outcomes, advance medical research, and set new standards in healthcare excellence. Through our agility, innovation, and reputation as trusted experts, we partner with the rest of Providence and its affiliates to advance a healthier future for all.

Step 5: Designing

Because the vision activity was integrated into a pre-existing strategic planning exercise, we didn’t do a traditional options development exercise. The hope was that presenting the futures stuff early in the process would lead to it permeating the rest of the discussions. I worked hard to facilitate this by making a big poster for each scenario, I put together an 11x17 poster for each of the scenarios including the visuals, the narrative, and the key implications, had them printed, and then taped them up around the room so that people could refer back to them.

Overall the futures work was used less than I hoped in developing the strategic focus. There was a lot of momentum and organizational muscle memory supporting a one-year planning timeframe where the prior year’s goals are evaluated and adjusted for the next year, and this didn’t alter that trajectory much. In future years, it’s clear that we need to get buy-in to weave Foresight more deeply into the core assumptions, planning, and expectations of the planning process.

Step 6: Adapting

The last stage of Foresight work is how we carry forward all the great stuff we did, build on it, and use it to change the organization. This work is still ongoing, but includes:

Sharing the work internally with the entire team but also various other groups, including the enterprise strategy/planning function, to see if more of Providence is interested in an approach like this at a broader scale11.

Sharing externally, first in niche Futures locations (including this newsletter, right now!) and, as we see value in the work, more broadly.

Setting up monitoring for signs that we’re moving toward one of the scenarios.

Scanning for signals as part of a small update project.

Making futures-relevant goals, and improve futures literacy in the department.

Final Thoughts

This entire process was a huge gift, both as a way to focus my emerging futures skills on my own industry, and as a pretty safe environment to get on-the-ground experience leading a project: having to evaluate what’s working, when to pivot, the best way to solve problems, etc. If you’d like to hear more, or think it might be fun to try something like this where you work, I’d love to talk.

This is, I am convinced, an essential trade secret of every futurist. If you’re looking to build one of your own, you could probably do worse than extract from this massive set of 2025 trends from Amy Daroukakis, Ci En Lee, Gonzalo Gregori, and Iolanda Carvalho.

The whole event was 2 days: half a day for orientation to drivers, then constructing them as described; a half day where we took an abortive attempt at systems mapping, then did the cross-impact and judged the impact and uncertainty of each driver; then the second day was about reviewing and tweaking the prior day’s work, agreeing on an approach to scenarios, and sketching the basics of each scenario for development later. The whole thing wrapped up a couple hours early on the second day, due to things proceeding at a good pace and the team being mentally exhausted from everything we’d done.

This could happen either as a result of aggressive Congressional action, or as a result of inaction (debt ceiling failure, etc).

In our work we named this company New Haven Health as a nod to Haven, the short-lived attempt from Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JP Morgan Chase to transform healthcare, or at least get benefits costs under control. The fact that New Haven pizza is objectively the best kind is unrelated (but I assume would influence their branding.

This is probably a pretty consistent problem inside any enterprise that maintains its own IT perimeter, so I would encourage this precaution early on in every project.

Going further, one of the things I will definitely do in the future is start by making a map of all the artifacts that will be created in the process, including a directed acyclic graph showing how earlier work will be used as input in later work. This serves the purpose of making sure none of the work gets “orphaned” by being created but never used, and it also serves as a reminder of all the previous artifacts to use as inputs for each step.

Or, possibly, an indication of what assumptions we weren’t willing/able to question, but the team wasn’t interested in exploring that angle and I wasn’t sure how productive I could make it.

I agree with you, this wasn’t enough time. But you take what you can get at these sort of things.

The full list of questions are in section 4.3.1 of Thinking About the Future, and apparently come from Peter Senge.

Maybe they even need a whole Foresight department, led by an ambitious, professionally trained futurist…