This week we had a guest lecturer and discussed a very different theory of change. Juli Rush is the director of the University of Houston’s Foresight Activation Lab, a death doula, and she teaches foresight to middle school students. I’ve written about Juli and her work in the past, and this was a good opportunity to hear about how the different strands of her work connect and tie to other work being done in the field.

Grief, trauma, and loss intersect with futures in a few ways. Trauma is variously associated with1 “foreshortening the future”, or even causing the individual to be stuck in past events, limiting the ability to meaningfully participate in futures work. Approaching from the other causal direction: futures work, by exposing how the future may be very different both from today and from the “official future” that’s expected, can threaten the security and maybe even the existence of the intertemporal plans people have established for their own security and that of their loved ones. In other words, foresight work often brings people face-to-face with loss and grief in advance, and ignoring the emotional consequences of this can limit our effectiveness2.

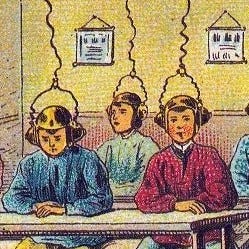

Juli has spent a lot of time turning to the power of ritual as a way of processing the grief and loss associated with futures, or, we might even say, harnessing grief to drive change. On her website, you can see how she uses a tarot-ish deck3 to guide people through some of these: according to van Gennep, rites of passage follow a traditional pattern of separation, transition4, and then incorporation (check out minor five); the ars moriendi are a medieval handbook on “good death” and can be adapted to help people through other kinds of transitions (see minor three); etc. Juli’s hope is that by building death and loss into our futures from the beginning, we can help build a world that allows things to die well.

Bonus Content: Megalopolis

Speaking of trauma, I was one of perhaps 150 people who saw Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis in theaters5. Please do not watch this film, it is very bad. I will enumerate only a few reasons:

It’s about the United States as modern Rome, or is it just about New York City as modern Rome? Both are implied, and not in any way that makes sense. Also, sometimes the downstream logic means that names are Roman, and sometimes it doesn’t. Also, exactly once, people speak Latin, but it’s not clear why. Also, they quote a lot of Marcus Aurelius, but also without any clear underlying philosophical motivation. Also, the writing is so overwrought and the lines are delivered so stiffly and theatrically6 that you can’t tell if the characters are quoting from an ancient source or not until they decide to give you the citation.

A fair amount of exposition and transition is handled by placards with words on them. Sometimes, Laurence Fishburne reads these aloud with as much gravitas as the subject matter will allow. Sometimes, you have to read them yourself. There is no underlying logic. At some point your rational mind will surrender.

There are living statues in the movie, which are an interesting visual idea, but they do nothing other than “be sad”, are only in the bad part of town, and like so many other ideas, the movie seems to completely forget that they exist after their single scene.

The film’s idea of subversion of expectations includes, most ridiculously, having Shia LeBeouf, notorious for saying “no no no no” in films, to say “yes yes yes yes” instead. I haven’t seen anyone else talking about this online, so consider it my original contribution to film criticism as a discipline.

But I walked into what I knew was an epic disaster of a movie because it also promised to be about what it takes to have a compelling vision for the future and to persuade people to commit to it. The film builds this up as the conflict between the protagonist, who wants to leave behind the weight of the past and build something new, and the antagonist who wants to keep things as they are and appeal to people’s baser instincts7. But then the big reveal happens on the thesis for what a compelling future looks like and it’s deeply disappointing; 1) it includes magic — literally a living building material that also provides energy8, 2) the film pulls the emergency brake and literally says that the vision for the future is “just starting a conversation”, which is to images of the future what “I’m just asking questions” is to 9/11 trutherism: a lame way to act smart but not have to show your work or be open to scrutiny. I will never get those 138 minutes of my life back, but as the film moves to streaming, I wanted to save the rest of my futures and futures-curious readers from the same fate.

The definition of trauma is pretty slippery, and I want to lean into the entirety of the semantic space rather than pick any specific meaning.

And, in turn, spending too much time working with the stories of people struggling with great change can impart secondary trauma to foresight practitioners,

Combining futures concepts with skeletons to get you in the mood to talk about death, naturally.

The transition is the liminal space that I’ve talked about before in the context of systems. Indeed, in many rituals people are literally carried over a threshold between the old and new worlds, and metaphorically it’s easy for people to float away; we need to help anchor them.

Does this trivialize all the reverence and respect for grief and trauma in what I wrote in the prior section? Is everything I say and do just a setup for the next joke? These are the just some of the levels of ego deconstruction you’ll have to go through in the aftermath of watching Megalopolis.

I think? He’s trying to build a casino, and gets grumpy when people talk about their dreams.

And also stops time maybe? Adam Driver has this ability but I can’t remember if it’s ever explained (and it’s never actually useful).