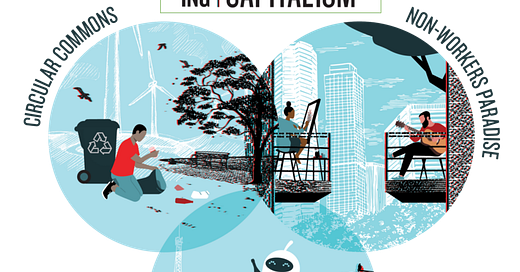

I recently finished reading Andy Hines’s latest book, Imagining After Capitalism. It distills his decades of research on the future of work, technology, and the environment into a detailed exploration of three overlapping images of what the next economic system may look like1.

Andy starts by sharing his own theory of change which informs the book. It is primarily developmental, meaning society is building toward something (without judgment about whether that’s good or bad i.e. not automatically “progress”), acknowledging that there may be cycles of iteration, collapses that arrest or reverse development, or various flavors of postnormal strangeness. In doing this, he explicitly pushes back against the postmodern aversion to overarching narratives. Capitalism represented a major development from the economic system that preceded it, and it’s increasingly looking like it will be replaced by something new in coming decades.

But there’s no reason to think this change will be smooth. For one thing, there are parties benefiting from the current system (and they’re rich!). Second, capitalism, probably like prior systems, has a narrative of inevitability, based around scarcity and competition2. But most of all, society has been drifting without positive alternate images of the future, which Fred Polak diagnosed as a peculiar disease of our time seven decades ago. The book aims to occupy this niche — by researching the various fragments of ideas about what a post-capitalist system might look like, Hines distills the conversations into three “big stories”, each focusing on replacing one of the core problems capitalism presents.

Even though the beating heart of the book is the three images fleshed out, and the paths that might lead to them, there are other interesting pieces I can’t bear not to mention. One is the identification of the seven key drivers of change: the shifting of values toward postmodern3 and to some extent integral values, with emphasis on ideas like “enoughness”; the acceleration of technology, including the ongoing digital transformation and the incoming bio/nano/robo revolutions; the growth of income inequality, which erodes asabiyya; automation, and whether we can keep finding enough jobs for people to do (and whether they will be meaningful); the challenge of finding new growth areas for the economy, and the potential crises and stagnation if we don’t; climate change and carrying capacity, and whether anything other than a collapse is even possible; and the Left’s inability to be an effective political force, due to factors from their obsession with the local to insistence on ideological purity.

But the most interesting finding was that, in reviewing historical transitions between archetypes, falling from a Baseline into Collapse usually meant a longer path to Transformation (often “stalling”) than finding a New Equilibrium. Basically, don’t trust the people saying we have to burn it all down to build something new, no matter how cool they look in their Che Guevara t-shirts; just build the future you want, one piece at a time.

Image 1: Circular Commons

This image addresses the rapacious consumption of natural resources under capitalism and the waste created as a byproduct. It solves the climate change and carrying capacity challenges by going beyond “sustainable” practices to a circular model where waste from one process becomes input for another, and the notions of private property expand to accommodate a world where much more of our shared resource/infrastructure base is managed as a commons. Instead of corporations, society is managed by NGOs, B-Corps, and similar organizations4. Whether the economy needs to actively “de-grow” or just stabilize is a point of contention between the ideas in this image.

Achieving this state requires two major changes to the modern paradigm: reconsidering the moral value of growth in society, including the tendency of capitalism to grow by enclosing more and more of the world which used to be outside the purview of the market5; the second is the current conception of humanity as separate from the natural world, both due to Western/Abrahamic ideas of “dominion” over nature, but also due to people spending more time in climate-controlled houses and cars rather than outdoors6.

The smoother transition to this future comes from a major rise in the importance/prominence/value of sustainability, either from the top-down with billionaires making capitalism more eco-friendly so they can stay rich without backlash (hydrogen-powered yachts etc), or from traditional sustainability ideas from the Green movement. The other option is a hard crash from growth overshoot — maybe due to climate disasters that cause a cascade of failures (food systems, the insurance industry, etc), or because the financial system crashes if we stop growing.

Image 2: Non-Workers Paradise

This image focuses on undoing the capitalist model of sorting the world into owners, who possess the means of production, and workers, who are obliged to sell those owners their labor to survive. This future undoes “jobs” as central facets of someone’s identity and gives workers more control and autonomy over their work through employee ownership, cooperatives, etc. But it also goes beyond this admittedly traditional 20th-century-Socialist vision to question the value of work itself; if automation is paired with robust compensation to those whose jobs are replaced, it could instead herald a strong UBI and a “full-unemployment” economy.

For this future to materialize, the Left must get its act together. The image requires people to broadly mobilize against inequality and demand redistribution at a systemic level, and that they take a more active role in their own lives and economic destinies. Both of these seem like fantasies in a world where an infinite amount of distraction, some of it even high-quality, is pumped into homes for $8/month. If Netflix is compelling enough that people aren’t having sex anymore, it’s hard to imagine them peeling away for a co-op board meeting.

The easier path to this future is via amplification of trends like the collaborative/gig/P2P/sharing economy7, elevating markets over companies, and empowering individuals directly as masters of their own labor8. The rough path is a more explicitly Marxist class war driven by increasing inequality and tribalism; as seen in Russia, France, China, etc, this is often a disastrous, blood-soaked approach to social change.

Image 3: Tech-Led Abundance

This image focuses on overwhelming the “scarcity” assumption at the core of capitalism. If we keep making technological advances, from normal product improvements to automation to free energy, and current exponential trends continue for a couple more decades, then our capacity rises so high that everything we care about becomes easily affordable and people just have “enough”9. This will require vast amounts of data as well as energy, so even if Information Society work is no longer at the top of the social hierarchy, it will still be a critical part of the transformation.

Note that this image isn’t particularly concerned with whether the system of the future system is “capitalist” or not — as long as everyone can get a massage gun for $10 from HyperTemu with same-day shipping, what’s the problem? The strategy for getting to this future is to reward entrepreneurs handsomely/obscenely for solving the “big problems”, so we can let competition work its magic.

The smooth transition to this future is that capitalism continues its three-century trend and finds new sources of value. By further monetizing and making products out of data, or experiences, or attention, or networks, or whatever, the makeup and narratives of the economy change, but its core essence remains undisturbed. Alternately, a tech-led collapse could come from something like a rogue AI, where a new superintelligent digital entity outthinks us like we outthink animals, and decides to treat us accordingly. AI 2027 is an example of the dumbest kind of AI that could do this, but we could also imagine a world where human populations and lifestyles are controlled by AI for the planet’s larger good, with occasional cullings and I’m not going to write the rest of this short story for you but you see the outline.

Conclusion

The book’s contribution is two-fold: first, it demonstrates that there are coherent, positive images of the future after all; second, it collates and organizes these visions into a framework that makes it easy to use as a reference. Of course, these images have significant overlap: for example, abundant clean energy feeds Circular Commons and Tech-Led Abundance, and automation fuels both Tech-Led Abundance and Non-Workers Paradise. I think it’s a valuable exercise to describe policy proposals, media, etc, by how much of each of these flavors they contain. For example, most Solarpunk futures are all-in on Circular Commons, have a strong Non-Workers Paradise undertone, and import Tech-Led Abundance as needed (solar panels at least).

Moving toward some combination of these images, while avoiding the worst collapse scenarios, won’t be easy. Hines acknowledges that, alongside efforts to evolve toward these new futures, it may be necessary to have more radical plans ready for a disaster/crisis that opens up new possibilities, or possibly pair responsible change efforts with a radical flank10.

Imagining After Capitalism is an essential reference for understanding how positive images of the future relate to one another, how we might get to them, and what dangers we may have to navigate.

Because people seem to like this kind of disclosure, I paid full price for the book — Andy’s writing about After Capitalism, but still needs to pay the bills today!

Though regular readers will know that Rianne Eisler posits that cooperative societies have existed throughout history on very different principles.

He also includes a side note on the Mean Green Meme, which is a particularly anti-social version of Postmodern thought: if all truth is relative, and my feelings determine what’s true for me, then anyone who disagrees with me is a bad person and I need to blame other people until everyone else changes so I’m comfortable. You can probably see how this is currently contributing to an ineffective Left.

This is closely aligned with David Ronfeldt’s view of networks managing health, welfare, education, and the environment, which I hope to publish an article about this summer.

This also had the unfortunate side effect of destroying hats as part of men’s fashion.

Hines notes each of these dynamics has an H1 capitalist-ish vibe and a very different H3 version, like eBay vs Buy Nothing.

This also maintains markets in their very valuable role as information generation/coordination devices.

It’s also possible that technological improvement attacks the problem from the other end as well, by transforming some subset of us into new kinds of human species that don’t need as much to be happy, like uploaded intelligence.

He also shouts out to Karl Schroder’s Stealing Worlds as an example of building an alternate system in parallel to the dominant one that can overtake it by degrees.

wow, that's a great review ... appreciate it!