Scenario Basics

We’ve been talking about building scenarios, but it’s worth taking a step back to understand the context and origin of scenarios. In two articles from HBR from 1985, Pierre Wack discusses the origin of scenarios at Royal Dutch/Shell around 1970. The term and concept of scenarios came from Herman Kahn’s work at RAND, and Wack adapted this for a corporate setting. His goal in introducing scenarios was to plan in a way that facilitated decision-making on a time scale appropriate for the life cycle of oil infrastructure (ie multiple decades). Being able to see the evolution of scenario complexity and utility by trial and error throughout the early years of Shell’s experience is fascinating. A few lessons: starting off with a baseline, similar to the forecasts the business has traditionally done, makes a scenario exercise less foreign to participants; the most important thing about a set of scenarios is that they cover the possibility space well, rather than a simplistic “high/medium/low” - the goal is to reframe the view of reality held by key decision-makers.

Scenarios are a tool for making future plans, but are they always appropriate? In 1997, Courtney, Kirkland, and Viguerie wrote an article, also in HBR, describing a taxonomy of future uncertainty. Rather than assuming the future is known and there’s a clear best strategy, or going to the other extreme and assuming the future is so fundamentally unknowable that the only option is to follow intuition, Courtney et al rank four possibilities by the level of uncertainty that remains after good analysis is done1: (1) a single future may be “clear enough” to make a single strategy; (2) there may be specific future events that will cause things to go in one of a finite number of directions; (3) there may be a bounded range of possibilities; or (4) the level of ambiguity may be so fundamental that it’s hard to even put bounds on the possibilities. In the first situation, a traditional forecast works fine; in the second, the predefined outcomes can be assigned probabilities or analyzed using game theory; building scenarios is perfect for the third; and in the fourth, leaders can identify leading indicators and look for analogies in other similar markets/industries. Per the authors, the vast majority of situations are in the second and third categories above, so scenario planning is frequently a relevant endeavor.

More on Baselines

This week we discussed a few more things about the baseline scenario. The first is a practical tip: once the contours for all the scenarios are generated, it’s easier to look back at the baseline and see if there are any places where you took too much liberty with an emerging signal. Most things that are experimental today will fail or still be experimental in the future, especially in baseline. Expect this scenario to feel boring - it’s based on the current state’s trajectory, not the current state’s wishes or goals. If you find yourself using words like “shift” or “novel”, you’re probably doing it wrong; words like “continue” are much more on target.

The second issue relates to our current era of polycrisis, where many things seem to be breaking at once. Often, the baseline for the future of many different domains will read more or less like a Collapse scenario, because lots of different systems (climate, water, international stability, political polarization, democratic norms, civil society) are simultaneously trending in negative directions. If this is your baseline - that we’re currently heading for disaster - then instead of doing a similar or slightly worse Collapse, build out a second New Equilibrium or Transformation scenario. One approach would be to imagine one Transformation scenario that arises from the Baseline-Collapse and another that emerges from the New Equilibrium, and another would be to build a New Equilibrium scenario showing compromises being made to salvage the current system, but anything that sufficiently explores the plausible space is fine.

One old method for charting the baseline consensus and the plausibility space, and one that’s currently regaining popularity, is Delphi. According to Theodore Gordon, this is another technique that came out of RAND. The first step is a set of quantitative questions about the future - these might be the year something will occur by, how likely a certain state of affairs is in X year, how desirable this event/state is, how prepared individuals/institutions are for it, etc. Then these questions are individually posed to an anonymous group of experts, who answer the questions and give justification. Then all the experts are shown the results of the first round (distribution of answers and justifications) and asked the same questions, to see if hearing the ideas and reasoning of other experts will lead to a greater degree of consensus. The output of this process should be a quantitative description of a reasonable baseline - it should map well to the “official future” unless there’s a huge disconnect between the public and experts.

Transformation

All this brings us to the building of the Transformation scenario. This is often the most difficult scenario to write2, because it has to stretch the client’s view of possible futures as far as possible without snapping due to implausibility. Early in Intro, I discussed Wendy Schultz’s phrase for this: “the knife edge of usability”3. Plausibility for a scenario boils down to a few issues: the scenario internal coherence (it’s not self-contradicting), the existence of some evidence (weak signals, etc) that supports its contours, aligning the amount of change to the time horizon of the project4, and the client’s own tolerance for imagination5. Because the goal is to evoke the breadth of the space of possible futures via these specific scenarios, building something that’s provocative and gets into the heads of decision-makers is more important than being “accurate”.

Bonus Content 1: Participatory Play

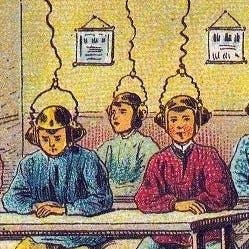

For several years, Aaron Rosa and John Sweeney ran a project called Gaming Futures that developed and experimented with several ways that the mechanics of games and structured play experiences could be used to broaden participation in futures work by the people that will be most affected by the decisions. One important observation they made is that the very nature of a game involves a kind of exercise in shared governance: in order to play, the various players have to agree to participate in the logic/frame of the game and abide by the rules6, so it’s helping to lay a groundwork for participatory futures more broadly. In “serious” settings, the terms “game” and especially “play” can be seen as unserious, so a certain amount of creativity may be needed (their example was calling a game an “enhanced survey tool” in one engagement). The other keys to success are to make sure the experience is appropriate for the participants and will result in something useful to the people digesting the results - this has implications for the rules design, components, and more. Ideally, the rules are simple enough to be taught within 5-10 minutes, but allow strategies to emerge that create real insight about the systems being simulated and how we might build the futures we want to live in.

Bonus Content 2: Wild Cards

One of the student presentations this week covered Elina Hiltunen’s thoughts on wild cards7. This, like so many terms in Futures, is kind of slippery because it has a vague everyday meaning as something that would either be unpredictable or have an unpredictable impact. Hiltunen explores some of the definitions in the field: events with a low probability but high potential impact, events that are startling/surprising with important consequences, sudden events that can change the course of a trend, etc. Part of the problem with the “surprise” aspect of the definitions is that it is now defined in relationship to an audience: surprising to whom?8 Hiltunen consolidates these ideas into defining wild cards as events that could occur without having enough time from when the event occurs to prepare/adapt/react to it9 - surprises that give more advance warning are just labeled “gradual changes”. Her canonical examples include natural disasters like hurricanes or asteroids as well as stock market crashes. So much of this boils down to an assessment of credibility - the credibility of weak signals of change determines whether that change will be a surprise, who will be surprised, and how justified those people will feel in having ignored it.

Some uncertainty (lack of information or understanding, bad theories, incorrect assumptions) can be resolved by analysis; others, such as the behavior of chaotic systems and the results of human choice, are irreducible.

In a more optimistic age, the Collapse scenario might take this role, for the same reasons.

In her paper, Schultz actually suggests that that knife edge lies beyond politely plausible scenarios in what she calls “crazy futures”, but I don’t think I’m nearly skilled enough for that yet.

If there’s some big transformation that really doesn’t have enough time to unfold in your horizon, an easy solution is to use language like “on the path to”.

In other words, the point at which they label it “science fiction” and shut down.

In ludology this is referred to as the “magic circle” - essentially the boundary between our world and a world where the game’s objective matters, the rules apply, and we have permission to do things we wouldn’t normally do - from tackling another human who poses no physical threat to you (football/rugby), making alliances with other players and then shamelessly betraying them (Risk), etc.

I think keeping this as a single-word “wildcard” is more natural, but I seem in the minority and will respect the two-word convention (at least for this paragraph).

As a classic example of this, the pandemic was treated as a huge surprise by most people, but people such as Bill Gates have been warning about something like it for years (his current place at the center of conspiracy theories just goes to show that being right about these things isn’t all it’s cracked up to be).

The noisier the signals, the longer it will take to notice them, which makes them more likely to meet this criterion.